Source: PigHealthToday.com

On the farm, swine caregivers tend to lump umbilical hernias and umbilical abscesses under the single category of umbilical defects. It’s likely that different factors are responsible for their development, but exactly what those factors are remain more speculation than fact.

What is common between the two types of umbilical defects is that the affected pigs are considered blemished and often are unmarketable through traditional channels.

“When these pigs come through the plant, packers have to slow down line speeds,” Mindi Bracy, veterinary student at Oklahoma State University, told Pig Health Today. “So, these pigs are often euthanized.” Depending on the farm’s defect prevalence, losses can add up quickly.

Bracy set out to study the risk factors for umbilical defects, which according to a global literature review range from 0.4% to 6.7%.1

Her research objectives were twofold: to understand on-farm risk factors that impact umbilical hernia and abscess incidence in 10- to 12-week-old pigs, and to identify associated bacterial populations and antibiotic sensitivities to guide judicious use.

Laying the groundwork

The study took place within a large commercial production system that recorded umbilical defects in 3% of its pigs. Data from the previous 6 months were used to select contract farrowing farms that had a high incidence and a low incidence of hernia defects. In all, 11 sow farms with the same genetic makeup were enrolled in the study.

Bracy visited the farms four times to observe and collect data from factors thought to impact umbilical defect rates. The period ran from birth to 12 weeks of age in two batches per farm, for a total of 22 collections. “I was blinded to the study so I didn’t know which farms were in which category,” she said.

The first visit occurred just after power washing and before sows entered the farrowing room. Bracy collected information on farm and farrowing room characteristics and management, as well as farrowing room equipment and protocols, including washing and disinfecting.

She also assigned a farrowing room cleanliness score, with a post-washing bacterial swab test ahead of batch 2 observations.

The second visit took place at the end of farrowing as piglets were processed. Bracy focused on management steps such as farrowing induction, navel-cord handling, use of a piglet drying medium and split-suckle protocols. She also assessed piglet processing practices — piglet age, tool cleanliness, antibiotics given, crate cleanliness and litter scour score.

The third visit followed the pigs into the nursery, where Bracy counted the number of hernias at weaning and necropsied any identified. During the fourth and final visit, she evaluated the pigs at 10- to 12-weeks of age and again counted hernias and conducted necropsies.

“Samples for bacterial isolation and susceptibility testing were collected from all pigs with umbilical abscesses,” Bracy noted.

The results

Of the pigs necropsied for umbilical defects between 3 and 12 weeks of age, about half were true umbilical hernias and the other half were abscesses. The bacteria isolated included Trueperella pyogenes, Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp. and Pasteurella multocida, Bracy reported.

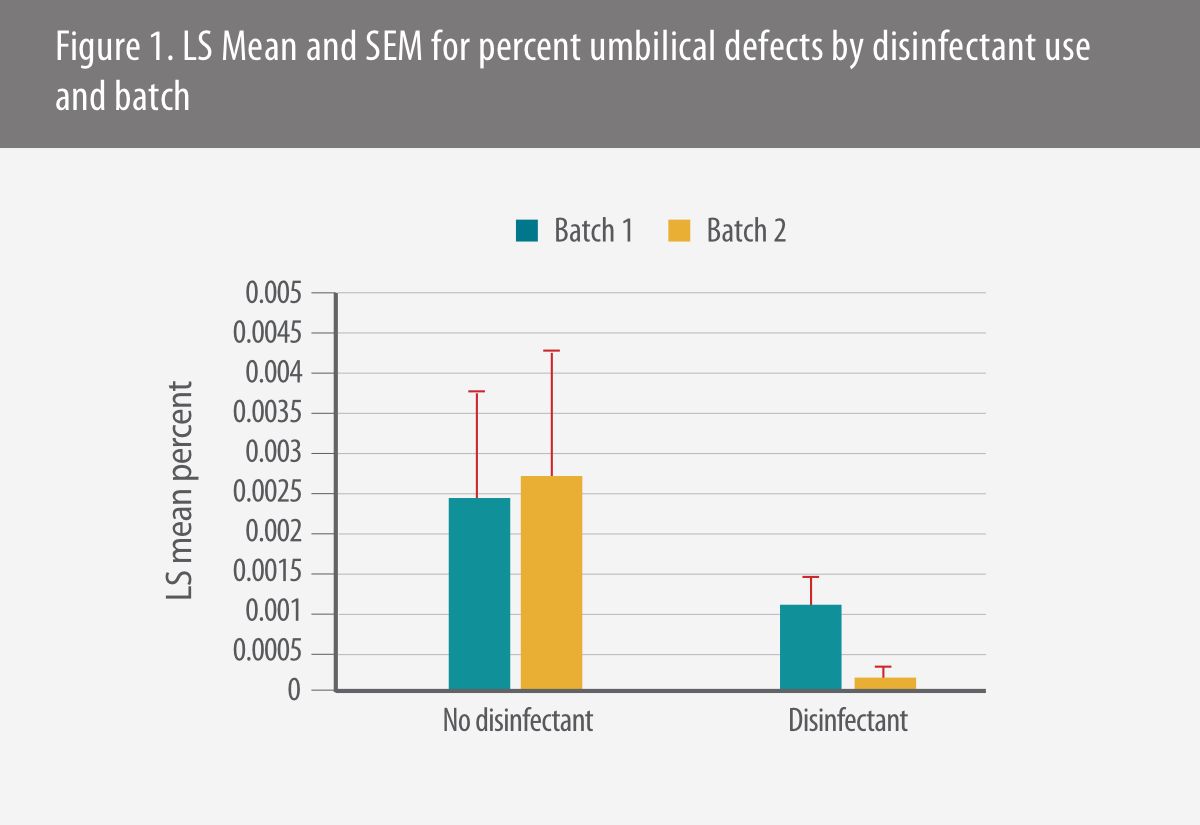

“After analyzing all the observed factors, only batch and disinfectant use were found to be significant for predicting umbilical defects,” she said.

For example, the odds of umbilical defects were 2.43 times greater for batch 1 compared to batch 2, while the odds of defects were 6.03 times greater when a disinfectant was not used.

Analyzing the interaction of batch and disinfectant, the odds of umbilical defects were 16.90 times greater when disinfectant was not used, she added.

“This is the first time that disinfection practices have been associated with the umbilical defect rate,” Bracy said. “If a farm did not disinfect, the proportion of pigs with umbilical defects remained very constant, and at a higher level than farms using disinfectant.”

Interestingly, for farms that used disinfectants, umbilical defects were even lower in batch 2 pigs. “It could be because they knew I was coming and they changed something in their protocols,” she added. “There was a month between batches, so there could be undetected factors, such as a change of season.”

Because 50% of the defects were true umbilical hernias, Bracy said it raises the prospect of genetics versus infection as possible risk factors. “Following boar genetics in association with umbilical hernia incidence would be a helpful aspect of future research,” she noted.

1 Bracy M, et al. Risk factors for umbilical defects in commercial pigs. Student Research Presentations, 52nd Am Assoc Swine Vet annual meeting. 2021;80-82