The USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) indicated in its October Oil Crops Outlook report that, “Brazil planted 38.6 million hectares of soybeans in the 2020/21 marketing year. With yields reaching all-time highs of 3.55 tons per hectare, Brazil produced a total of 137 million metric tons of soybeans. Despite high production numbers in the current marketing year, exports are lowered by 350,000 metric tons to 81.65 million metric tons as Brazil’s main trade partner, China, has slowed their soybean purchases. Brazil is expected to store these soybeans, raising October 1 beginning stocks for the 2021/22 marketing year to 26.95 million metric tons which is up 7 million metric tons from last year.”

More narrowly, the Outlook report stated that, “China has experienced power shortages/outages in many of their northern provinces in recent weeks.

Not only has this situation undoubtedly affected the country’s entire food marketing system, but effects are also seen reverberating throughout the global oilseeds market since China is the leading importer of soybeans.

“The 2020/21 Chinese soybean crush was lowered by 1 million metric tons to 93 million metric tons. Domestically, crushing facilities housed in China’s affected regions may have been impacted. As such, China is expected to maintain a healthy supply of soybeans totaling 153.723 million metric tons, carrying an additional 925,000 metric tons of soybeans into the new marketing year. Whether the power shortages in China are short- or long-lived remain to be seen; however, as discussed above, typical trade partners (i.e., Argentina, Brazil, and the United States) have felt immediate impacts.”

Bloomberg News reported last week that, “China will release state reserves of diesel and gasoline to ease supply shortages, in the latest step to combat an energy crunch that’s threatening economic growth.”

“China last month released crude oil from its strategic reserve for the first time in an unprecedented intervention to lower prices. Surging energy costs and electricity shortages have forced many factories to suspend production, weighing on the country’s industrial sector and increasing the risks of inflation,” the Bloomberg article said.

A separate Bloomberg News article late last month reported that, “Vegetable prices have soared in China in recent weeks, costing more than meat in some cases, and creating another headache for consumers already hit by power shortages and strict virus curbs.”

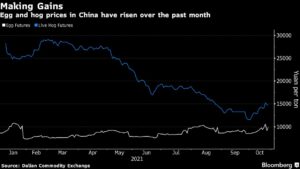

“The rally is so strong that China’s agriculture ministry last week pledged to crack down on vegetable hoarding and to ensure stable supply,” the Bloomberg article said, while adding that: “Higher vegetable prices could become a broader inflation problem if the gains stoke bullish sentiment in agricultural markets and consumers switch to eating more eggs and pork. The Chinese government keeps a particularly close eye on pork prices as the meat is a staple and a crucial determinant of consumer inflation.

“There already appears to be a spillover onto the prices of proteins, with China’s egg futures hitting the highest level since July and live hog prices climbing more than 25% this month.”

Also with respect to Chinese pork prices, and production, Wall Street Journal writer Jacky Wong reported on Friday that, “After a rollercoaster-like two years, pork prices in China have come back to earth. Price swings have been magnified by two health crises—African swine fever and Covid-19.

But the collateral damage to small farms could actually make for a somewhat less wild price cycle in the future, as the slow consolidation of China’s massive pig-rearing industry takes another step forward.

“Hog futures in China have risen more than 20% from last month’s low, signaling a reversal of the sharp decline earlier this year. But that still leaves them far below the heady levels of 2019 and 2020. Hog prices have fallen by nearly two-thirds since January thanks to a one-two punch of oversupply and the low season for demand.”

The Journal article noted that, “The swine fever outbreak actually probably helped to accelerate consolidation in the industry since smaller farms are less able to invest in biosecurity measures. In fact, the number of the smallest farms had already dropped two-thirds from 2009 to 2019. Farms that produce 50,000 pigs or more nearly quadrupled over the same period.

“The trend will likely continue but the pace will still be gradual since too-rapid closures could affect income and employment in rural villages.”