Quick facts

Pork producers shouldn’t overlook the effects of heat stress. Heat stress causes

- Lower feed intake in grow-finish pigs during the summer.

- Harmful effects in the sow herd during breeding, gestation and lactation.

- Lasting harmful effects in offspring of sows that had heat stress during pregnancy.

It’s important to prevent heat stress to limit these harmful effects.

Heat stress affects both grow-finish and breeding pigs

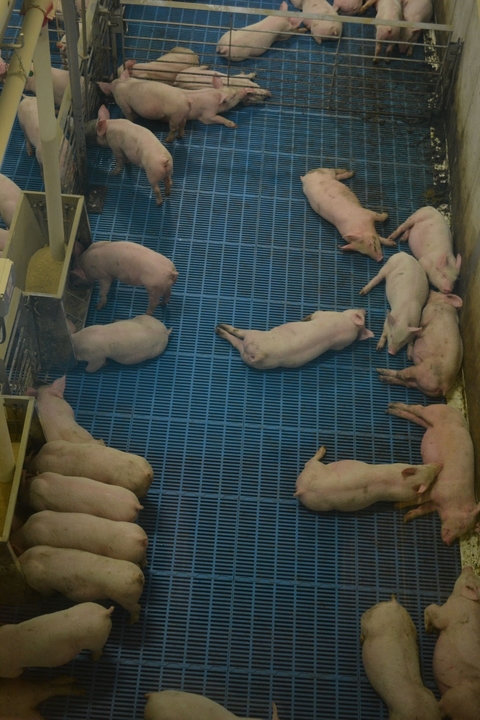

Pigs are more sensitive to heat than other animals because they can’t sweat. Thus, high temperatures can lead to heat stress, which causes poor performance. Often, pork producers only think about grow-finish pigs when they consider the harmful effects of heat stress. In reality, heat stress also affects the breeding herd.

Dr. Steve Pollmann, Vice President of Smithfield’s Hog Production Division (formerly Murphy-Brown LLC.) estimated heat stress costs the American swine industry $900 million each year. Of that, about $450 million of loss is in the grow-finish stage and about $450 million of loss is in the breeding herd.

Ideal temperatures for housed pigs

As a pig gets older and heavier, its ideal temperature declines, see the table below. Thus, heat stress is a greater concern in older finishing pigs (greater than 110 pounds), sows and boars than in younger pigs. Heat stress begins to affect sows, boars and finishing pigs at about 70 degrees F. If temperatures remain above 80 degrees F for more than two to four days, decreases in performance and reproductive efficiency can result if cooling relief isn’t available.

|

| Animal age, weight | Ideal temperature (F) | Desirable temperature limits (F) |

|---|---|---|

| Lactating sow | 60 | 50 – 70 |

| Litter, newborn | 95 | 90 – 100 |

| Litter, 3 weeks old | 85 | 75 – 85 |

| Nursery, 12 – 30 lbs. | 80 | 75 – 85 |

| Nursery, 30 – 50 lbs. | 75 | 70 – 80 |

| Grow – finish pigs | 60 – 70 | 50 – 75 |

| Gestating sows | 60 – 65 | 50 – 70 |

| Boars | 60 – 65 | 50 – 70 |

Seasonal infertility refers to the usual decline in production by sows that are bred during summer and farrow November through January. Summer heat events that lead to heat stress are the primary cause of seasonal infertility in the breeding herd. Despite the name, seasonal infertility doesn’t relate to reproductive cycle because domestic swine aren’t seasonal breeders.

Heat stress also harms production in sows during lactation. Increased environmental temperatures commonly reduces feed intake by sows. Lower feed intakes lead to depressed milk production, which then reduces piglet body weight gain.

Sows that experience heat stress

- 14 to 21 days before insemination may have a lower farrowing rate

- between 7 days before and 12 days after insemination may have a decline in total pigs born per litter

Effects of heat stress on sows

- Decreased farrowing rates

- Lower total born per litter

- Reduced number of piglets born alive per litter

- Reduced number of litters farrowed per week

- Reduced feed intake

- Lower milk production

- Lower piglet body weight

- Increased wean-to-estrus interval

- Failure to express estrus

- Higher embryonic death (if early gestation)

- Higher stillborns (if late gestation)

- Failure to maintain pregnancy

- Increased sow mortality

- Lower weaned pig throughout

Selection for increased leanness has led to an increase in heat production of growing pigs over the years. The more productive an animal is, the more heat they produce. This extra heat makes pigs less tolerant of external heat. As a result, they’re more prone to heat stress than less productive pigs. In response to heat stress, these pigs will decrease feed intake to reduce the heat they make. Reduced feed intake reduces growth rate.

Pigs raised in heat stress settings will have more fat deposits than pigs raised in cooler settings. Increased fatness results because the pig’s body will change how it uses nutrients. Nutrients are put towards more fat growth than protein growth in heat-stressed pigs consuming less feed.

Studies looked at the effects of heat stress experienced by sows during gestation on the piglets in the sow’s uterus. Piglets born to sows that experienced heat stress during pregnancy will have increased core body temperature, which makes them more prone to heat stress after birth. Changes in metabolism also occur in these offspring, which results in less skeletal muscle and more fat tissue being deposited during the growth stage.

Effects of heat stress on growing-finishing pigs

- Reduced feed intake

- Decreased body weight gain

- Inconsistent market weights

- Decreased feed efficiency

- Higher carcass fat deposits

- Reduced carcass quality

Baumgard, L. 2015. Assessing the impact of seasonal loss of productivity. National Pork Board Animal Science Webinar. (Accessed 14 October 2015).

Bloemhof, S., P. K. Mathur, E. F. Knol, and E. H. van der Waaij. 2013. Effect of daily temperature on farrowing rate and total born in dam line sows. J. Anim. Sci. 91:2667-2679.

Johnson, J. S., M. V. Sanz Fernandez, J. F. Patience, J. W. Ross, N. K, Gabler, M. C. Lucy, T. J. Safranski, R. P. Rhoads, and L. H. Baumgard. 2015. Effects of in utero heat stress on postnatal body composition in pigs: II. Finishing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 93:82-92.

Lay, D. 2010. The physiologic response to stress and its effects on swine reproduction. Midwest ASAS Billy N. Day Symposium. (Accessed 20 October 2015).

Myer, R. and R. Bucklin. 2001.Influence of Hot-Humid Environment on Growth Performance and Reproduction of Swine. Pub. AN107 UF/IFAS Extension. (Accessed 29 October 2015).

Pollmann, D. S. 2010. Seasonal effects of sow herds: industry experience and management strategies. Midwest ASAS Billy N. Day Symposium. (Accessed 20 October 2015.)

Williams, A. M., T. J. Safranski, D. E. Spiers, P. A. Eichen, E. A. Coate, and M. C. Lucy. 2013. Effects of a controlled heat stress during late gestation, lactation, and after weaning on thermoregulation, metabolism, and reproduction of primiparous sows. J. Anim. Sci. 91:2700-2714.