Much of my Extension swine work since 2018 has included and revolved around biosecurity education and foreign animal disease preparedness. 2018 was the year when, in August, the swine world learned of the outbreak of African Swine Fever (ASF) in China. ASF is a swine hemorrhagic disease which originated in wild pigs in Africa. Over the past 50 years it has broken out in portions of Eastern Europe, Asia and Africa. In the 1970s and 1980s it was identified and later eradicated in Cuba, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic (DR). ASF is not a human health problem, but it is lethal to pigs.

In late July 2021, ASF was confirmed in the northwest part of the Dominican Republic. A month later, it was positively identified in pigs in Haiti. Haiti and the Dominican Republic are the two countries on the island of Hispañola, and their shared border is highly porous. Suddenly we were facing ASF in our hemisphere. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and its Animal & Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) already had a working arrangement with the Dominican Republic to provide disease testing and assistance with their Classical Swine Fever (CSF) outbreak. At the request of the DR government and health officials, USDA and APHIS began to assist with the issues surrounding the new ASF outbreak.

Fast forward to mid-March 2022. An opportunity crossed my path which seemed to fit with my skills. Farmer to Farmer, a US-AID funded program at Partners of the Americas, was seeking a volunteer to work in the Dominican Republic for fifteen days in April. The project focused on teaching smallholder pig farmers about ASF and biosecurity. I submitted my application, and with permission from the University, a current passport, up-to-date COVID vaccinations, and an adjustable schedule, I learned that they wanted me in the DR in mid-April.

Because I was going to a place where ASF was active, I planned a wardrobe that would not return to the US. I obtained a pair of walking shoes which wouldn’t come home, and picked up several clothing items at a nearby Goodwill. Two of my UMN College of Veterinary Medicine colleagues, Dr. Marie Culhane and Dr. Cesar Corzo, helped me prepare for the project. Both had international pig experience and shared with me what to expect. Conversely, we planned for information I could bring back to them.

The project host was an international cooperative development organization, PROGANA, who has a 100-year history collaborating with producers and cooperatives between the US and the Americas. In early April our scope of work adjusted. The plan morphed into a Train-the-Trainer project wherein I would work with veterinarians and other agency personnel who would then take the message to the small pig farmers across the country.

For me it was a relief that I wouldn’t visit ASF infected farms and pigs, but also a disappointment that I wouldn’t interact directly with those smallholder farmers. I left Minneapolis early on the icy Monday morning after Easter, April 18, and the whirlwind began!

PIGGYBANK FARMERS

The Dominican Republic has a population of about 10 million people and 1.9 million pigs. In the Dominican swine industry, roughly 20% of the pig farmers raise 80% of the pigs in US-style “modern” facilities. Conversely, 80% of the pig farmers raise 20% of the pigs on small farm or in backyard settings.

In the DR, those smallholder pig farmers (80% of all pig farmers) are termed “Piggybank Farmers” because their pig operations provide a liquid funding source for their needs. If they have to pay school fees for their children, they sell a pig. If they need vehicle repairs, or to pay medical bills, they sell a pig. In many cases, these piggybank farmers’ pigs roam freely, and often there is a “village boar” who is shared from herd to herd for breeding purposes. These farmers commonly feed their pigs garbage, and they obtain the garbage from Dominican hotels who host more than 2 million visitors to their resorts annually. The ASF outbreak has affected these pig farms the most.

The 20% of Dominican pig farmers who raise the majority of the country’s pork, in many cases are vertically integrated with a company slaughter plant. They feed their pigs balanced rations and practice exclusion-type biosecurity, use artificial insemination and have made significant investments in their operations.

GOVERNMENTAL SUPPORT

The Dominican government has worked directly with USDA and APHIS to address steps to take to eradicate ASF in the country. DR’s Ministry of Agriculture provides veterinary technicians to take samples and help confirm cases. The General Directorate for Livestock (DIGEGA) employs veterinarians who work directly with pig farmers across the country.

At the time of my visit, ASF was confirmed in 29 of the 32 provinces in the DR.

Discussion at the time circled around the options of destroying all of the ASF infected pigs. Should all piggybank farms be wiped out? How to start again? What happens to those families whose livelihood is obliterated?

I learned that many of the piggybank farmers didn’t think that ASF was really anything different than a usual sickness that caused their pigs to die. Veterinarians with whom I worked shared stories of entire villages losing their pigs, farm-by-farm because of a shared boar who spread ASF.

THE TEACHING & LEARNING BEGAN

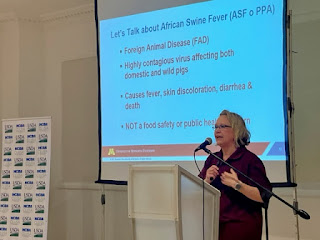

I had a myriad of ASF and biosecurity education information and spent the first days teaching a large group of DIGEGA veterinarians and technicians. For three days we covered the basics of ASF, biosecurity, methods of teaching adults, and possible alternative livelihoods. The information was familiar to them, but they typically did not formally teach groups. My mission was to prepare them to take the message throughout the country to their provinces’ pig farmers. We spent three terrific days of learning and sharing, role-playing and strategizing how to best get the message out to their pig farmer constituents.

PROGANA provided a simultaneous translation service for the entire project. Two translators and a tech guy set us up with ear buds daily. One translator spoke English into my earbud and the other translated my words into Spanish for the group. My high school Spanish skills were quickly revived and I relished the chance to (try to!) communicate with them in Español.

Back home Drs. Culhane and Corzo assisted my development of information about alternative livelihoods. Pig farmers in Eastern Europe and Africa who lost their herds were able to grow chickens, rabbits, goats or fish, so within the groups I met, we discussed the possibilities. We also plotted the pros and cons of a type of “cooperative” in a village where pig farmers would repopulate but specialize; set up sows and boars only on one farm and provide growing pigs to the other farmers. All of these suggestions have potential, but the details need to be worked out and then financially incentivized, most likely by the government.

In addition, I kept in touch with my UM Extension swine cohort, Sarah Schieck Boelke, who supplied additional materials I couldn’t access on my own.

With my Farmer to Farmer and PROGANA hosts, I toured the national laboratory, LaVeCen, where the USDA has assisted expansion of the lab which tests for ASF, and met Dominican and US technicians who process 600 samples/day with the capability of handling 2000 daily in a 24-hour turnaround time. We also visited JAD (Junta Agroempresarial Dominicana), the 40-year-old ag production cooperative and trade organization where one of their team members is currently developing a livestock biosecurity certification program for Dominican farmers.

I DID meet some farmers out in the countryside, at neutral locations. We traveled to Moca, in the Espaillat province, which hosts the highest population of pigs in the country, nearly 250,000. When I visited, they had already eliminated 10% because of the ASF outbreak. The farmers at the meeting were mid-sized producers who understood the importance of biosecurity practices and were open to the idea of sow farm cooperatives.

Later that same week we traveled east to La Romana to present the message to a group of producers and slaughterhouse personnel from the vertically integrated company AGROCARNE. Their company veterinarian brought everyone to the meeting, including the truck driver. In every meeting it was mightily apparent that truck cleanliness and biosecurity is a chink in the armor which needs to be fixed.

Throughout the two-week project I delivered the message, tailored to the specific audience of the day, including a Zoom call with an association of large modern-style pig farmers, AGROGRANJA. In total I made contact with 173 different producers, veterinarians and technicians.

REFLECTIONS & RESULTS

Throughout the project these important elements reappeared:

- DIGEGA veterinarians are ready and willing to spread the message to their pig farmers

- Trucks sanitation & truck driver biosecurity education is crucial

- Heat treatment of garbage fed to pigs is an important management step

- Educational and financial assistance to the piggybank farmers can help them get through the ASF disaster

- Education of young students will set the stage for avoiding an outbreak in another 40 years

- Establishment of a livestock census in the DR will help the government know exactly how many animals it is dealing with

- Remuneration for pig farmers is critical

- Development of an ASF vaccine may be a key in eradicating ASF in the Dominican Republic and Haiti

None of this will be simple or quick. Currently Farmer to Farmer and US-AID are working to put together additional Extension education-type projects to assist piggybank farmers and to work with cooperatives.

While I never made it to a sunny Dominican beach, I spent two fantastic weeks working with wonderful Dominican people who care about pig farming as much as I do!