Source: Bloomberg

Professor John McGlone of Texas Tech University trekked to Manitoba, Canada, in the dead of winter to warn hundreds of local pork farmers that the way they did business was about to change.

McGlone knew McDonald’s Corp., the world’s largest restaurant chain, planned to say it would only buy pork from producers who didn’t keep pregnant sows in gestation crates — 2-foot-by-7-foot stalls that don’t let the animals turn around and force them to excrete where they stand. Crates were standard for the industry that puts bacon and pork chops on plates around the world, but seen as cruel and unnecessary by a growing mass of critics and consumers.

“The writing is on the wall,” McGlone said he told the audience that night.

That was 22 years ago. Gestation crates are still widely used by farmers, and McDonald’s still buys meat from them.

One big reason the industry has clung to crates is cost. Producers say that changing practices forged over generations will lead to higher prices for meat. Another reason, they say, is confining pregnant pigs keeps them from being harmed by other pigs.

“Those things protect sows at their most vulnerable times,” said Steve Meyer, a consulting economist for the National Pork Board and the National Pork Producers Council.

That has made it harder for companies like McDonald’s to change. After McGlone’s speech, in January 2001, it would be more than a decade before the fast-food giant committed in 2012 to “ending gestation stall use” — by the end of 2022. The company has missed that self-imposed deadline. Other restaurants and meat producers have also promised to shun crates, but still, they remain ubiquitous.

The struggle shows how economics and corporate inertia can stymie change even when it is popular with consumers. The clash has now made its way to the US Supreme Court, where the pork industry is challenging Proposition 12, a California ballot initiative passed in 2018 that banned the sale of uncooked pork from hogs raised with crates that didn’t meet minimum size requirements, effectively ending their use for any producer looking to sell pork in California. The measure was set to go into effect last year, until a court order paused enforcement.

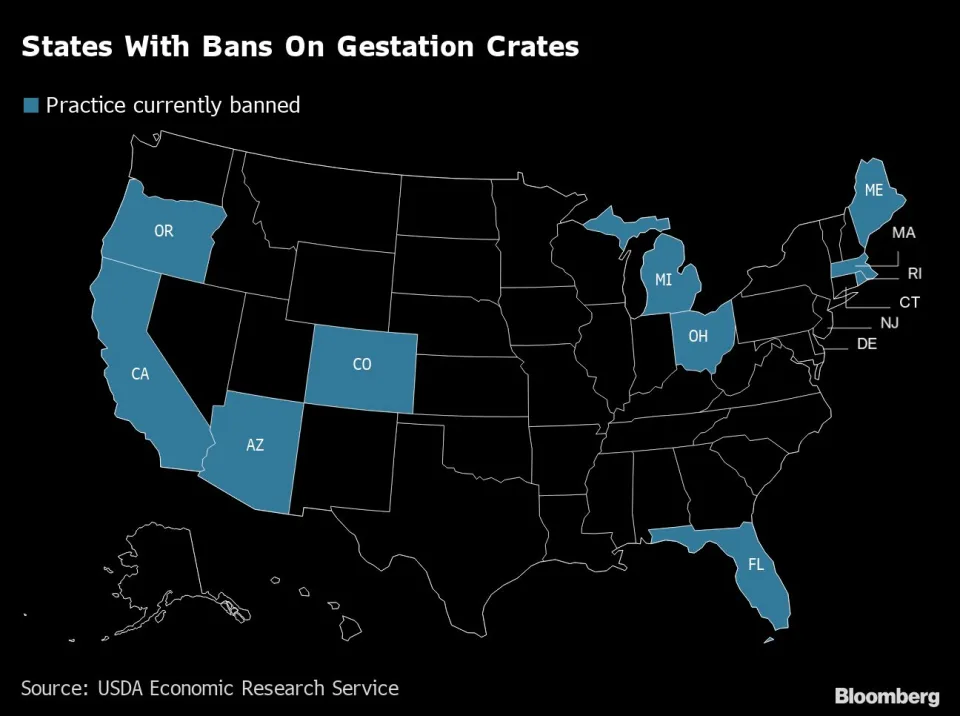

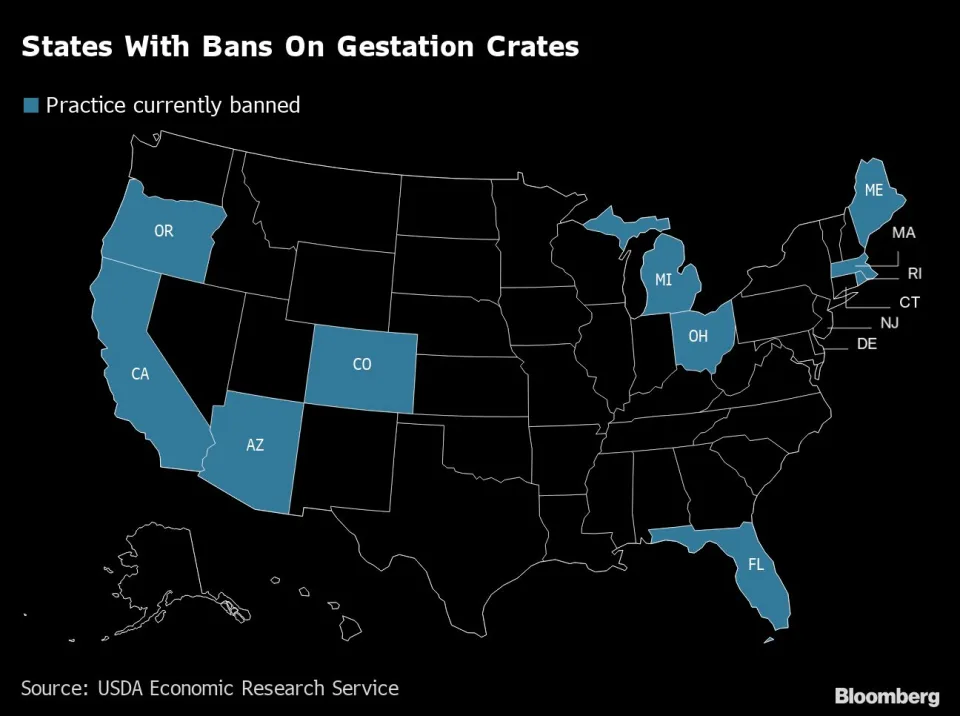

California accounts for an estimated 13% of US pork consumption, and nearly all of it comes from elsewhere, allowing the state’s law to impact farms beyond its borders. Combined with the 10 other states that have passed similar laws, by 2026, more than 17% of all hog producers would be subject to a ban if the California measure stands, according to a December report from the US Department of Agriculture.

A ruling is expected this term.

Momentum against gestation crates has been building for years. In 2002, Florida voters adopted a ban. In 2007, Smithfield Foods pledged to get rid of them. Burger King, Wendy’s Co. and other restaurants followed McDonald’s lead with their own plans to stop buying crate-raised pork.

Still, the end of crates looks like a distant prospect, especially in the first weeks of a mother pig’s term. McDonald’s said last February that it would push its 2022 deadline to 2024, and that the crates were only verboten after pregnancy was confirmed—which can take as long as six weeks after insemination. Even billionaire investor Carl Icahn, who lost a proxy fight over the matter last year, was unable to force the company back to its original promise of “ending” the use of crates.

A McDonald’s spokesperson said the company is making progress toward its 2024 goal.

Burger King owner Restaurant Brands International Inc. said that in the US it’s on track to remove confirmed pregnant sows from crates by the end of 2024, and it hopes to eliminate the crates for nonpregnant sows “in the long term.” Wendy’s, which had promised in 2012 to “eliminate the use of sow gestation stalls,” says it has met its commitment — but that it was and had always been just for “confirmed pregnant sows.” It didn’t respond to questions about the discrepancy between the original promise and its current policy.

Smithfield said it keeps sows in crates for 35 to 42 days after insemination.

Gestation crates didn’t become commonplace until they were added to new buildings in the 1980s. But by February 2000, when they appeared on the cover of trade publication National Hog Farmer with the headline “Breeding Herd Efficiency,” they were known for saving space, labor and, ultimately, money.

That savings, and the complexity of hog farming, has made the industry reluctant to shift. Pork producers have been slower to change than other farmers, like egg producers, who have been increasing their cage-free accommodations in response to mounting corporate commitments and consumer demand.

“A pig is going to be born in one place, moved someplace else and then when it’s slaughtered, there are many pieces to keep track of, so that’s different from an egg-laying hen,” said Maisie Ganzler, who oversees purchasing at Bon Appétit Management Company as chief strategy and brand officer and spent more than 10 years trying to source crate-free pork. She only recently succeeded. (Icahn had called for Ganzler to become a board member at McDonald’s.)

Another powerful force preventing a move away from crates could be habit.

“It’s stubborn pig farmers, basically,” according to Texas Tech’s McGlone, who says he faced significant pushback from producers after his Manitoba talk.

With the California case still to be decided, there are signs that the cost issues pork producers warned about are surfacing. The US hog herd has been shrinking in part due to uncertainty about California’s law, as well as elevated prices for feed and higher levels of pork supply than demand. Once a farm has gone crate-free, it can raise fewer pigs, said Russell Barton, director and product manager at Urner Barry, a food-trade publisher and commodity researcher.

“You need to build more space for them to have the same amount of production,” Barton said.

But there are also hints that the industry’s approach to crates is evolving.

Once the debate was whether gestation crates were a necessity; now the question has turned to how long to use them. In 2012, when McDonald’s said it would eliminate its crates, it told producers sows could stay in crates until they were “confirmed to be pregnant,” according to an April 2022 company filing. Verifying a pregnancy can take as long as 35-40 days. Other producers use them for much shorter periods, about 7-10 days after insemination.

Shana Beattie, a fifth generation farmer raising hogs for Smithfield, said she now uses the crates for seven days at most.

“Historically we learned that giving pigs individual care and keeping them away from the aggressive behavior was to their benefit,” she said. Now, she keeps them confined only just after insemination. Then, when they’re in a group, Beattie relies on technology such as ear chips to ensure each sow gets enough feed, a common cause of aggression. “We’ve learned that open pen gestation will work.”

The need for crates is “overstated,” according to Jim Wallace, senior director of fresh pork at Perdue Farms’ Niman Ranch. Wallace says giving animals more space — and farmers more discretion over how to manage animals — can keep pigs from becoming aggressive and assure pregnancies are successful. Niman Ranch, one of the few truly crate-free pork producers in the US, supplies major companies such as Chipotle Mexican Grill Inc. and Whole Foods Market Inc., as well as high-end chefs.

The Supreme Court is considered “unlikely” to rule in California’s favor, according to Bloomberg Intelligence, but there is some expectation that farmers won’t put crates in new buildings, whatever is decided.

“If they are building new facilities, they’re going to try to build in that flexibility,” said Christine McCracken, senior analyst for animal protein at Rabobank. “Whether or not these changes are legislated, they are going to try to build in the flexibility in the event customer expectations change over time.”

Josh Balk, chief executive officer at the Accountability Board, a nonprofit that tries to hold companies to their ESG commitments, is optimistic about the ruling — and the direction companies are going. He said even McDonald’s position is a big advance from where it was 20 years ago.

“There is still a ways to go,” Balk said. “But we should still recognize this improvement.”

In 2012, the National Pork Board estimated that moving away from crates would cost between $1.2 billion and $6.1 billion, or as much as 27% of the industry’s sales that year. “The longer the time horizon, the less the cost to producers and consumers,” it said. (The industry pegs the cost to farmers for compliance with Proposition 12 as significantly lower: about $300-$350 million.)

McGlone said the industry could have spent the money it used to resist change to implement it. Instead, he said, “they’re fighting it right down to the end.”