Written collaboratively by Ryan Samuel; Juan Castillo Zuniga, SDSU; Kevin Herrick, POET, LLC; and Melissa Jolly-Breithaupt, POET, LLC.

Corn-fermented protein (abbreviated as CFP) derived from dry-mill bioethanol production has demonstrated potential as a high-quality protein ingredient in weaned pig diets. In previous research, it was shown that high-protein, corn-fermented products have greater digestibility and metabolizable energy content compared to distiller’s dried grains with solubles (abbreviated as DDGS) and corn products. As an excellent source of lysine and methionine for young pigs, CFP can have up to 50% protein and 25% yeast. Benefits of CFP for the weaned pig due to the fermentation process include improved protein digestibility, increased energy digestibility, as well as a reduction in crude fiber levels compared to non-fermented protein sources.

Research from the University of Illinois has demonstrated that corn-fermented products have higher crude protein and amino acid (abbreviated as AA) content than soybean meal. Their findings resulted in similar standard ileal digestibility values comparing two levels of CFP and soybean meal. The CFP products contained greater concentrations of standardized ileal digestible AA (except arginine, lysine, tryptophan, and aspartic acid).

Because of the difference in the starting product (corn versus soybeans) and the desired end product (ethanol versus soy oil), corn-fermented protein and soy protein concentrate are processed differently. Corn fermentation involves using specific microorganisms, such as yeast or lactic acid bacteria, to convert the starches in corn into various compounds, including alcohol, organic acids, and gases. The fermentation process adds flavors, textures, and nutritional benefits to corn-based products. In contrast, soy protein concentrates are produced by extracting protein from defatted soybean meal using solvents or other methods. The extracted protein is then concentrated to increase its protein content. Starter diets for weaned pigs typically include specialty protein products to provide a higher concentration of protein and energy than grower diets, as young pigs have higher requirements for these nutrients to support growth and development.

Research at South Dakota State University

Methods Used

A trial was conducted with the objective of determining if CFP could replace soy protein concentrate in weaned pig diets with similar effects on growth performance and gut integrity at the South Dakota State University offsite swine commercial wean-to-finish research barn. Newly weaned pigs were distributed evenly into 44 pens, with 26 pigs per-pen balanced evenly by sex and an initial body weight of 13.2 ± 0.2 pounds (abbreviated as lbs). The four treatments were designed as a titration of CFP inclusion at 0%, 4%, 8%, and 12% replacing soy protein concentrate in Phase 1, which consisted of days 0 to 14, and each pig was fed 8 lbs. of the diet. Phase 2, from day 14 to 28, consisted of increasing levels of CFP with 0%, 2%, 4%, and 6% replacing soy protein concentrate, and 12 lbs/pig were fed. Pigs were fed a common diet through Phase 3 (50 lbs/hd budget) to the end of the trial. Gut integrity was determined by subjecting the pigs to a differential sugar absorption test (abbreviated as DSAT). This consisted of administering a 5% lactulose and 5% mannitol (15 ml/kg) solution to pigs consuming the 0% and 12% Phase 1 CFP inclusion diets on the 10th day of the trial. Urine was collected to measure differences in sugar ratios to assess gut permeability.

Findings

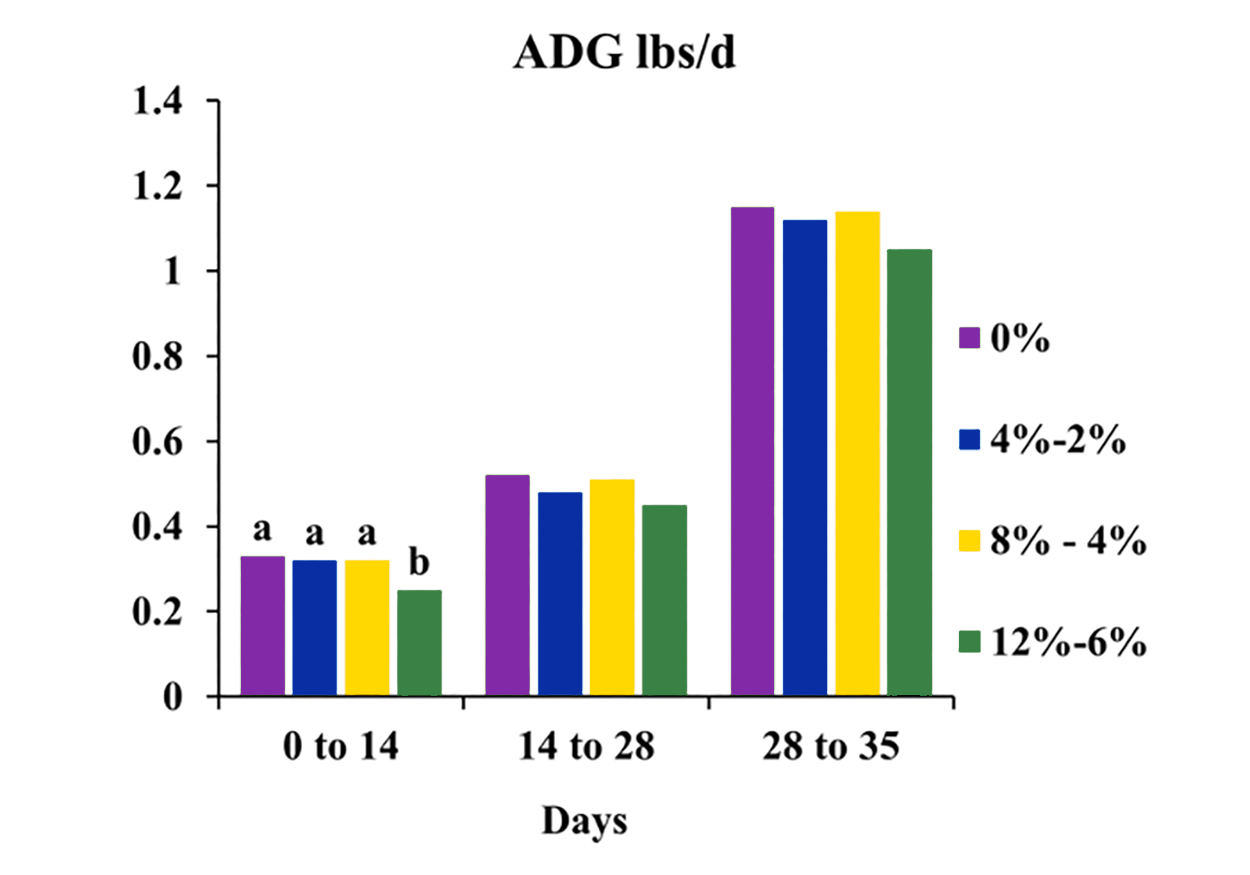

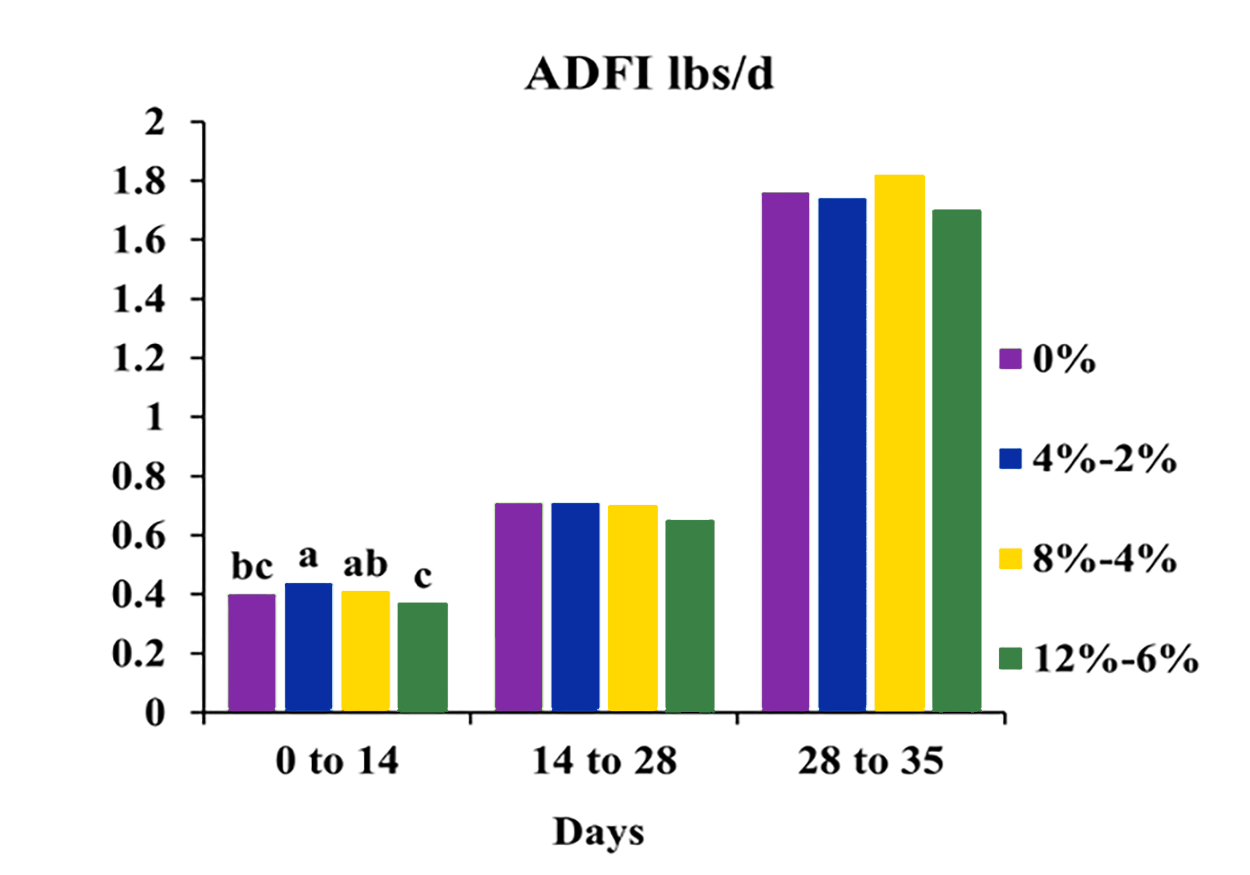

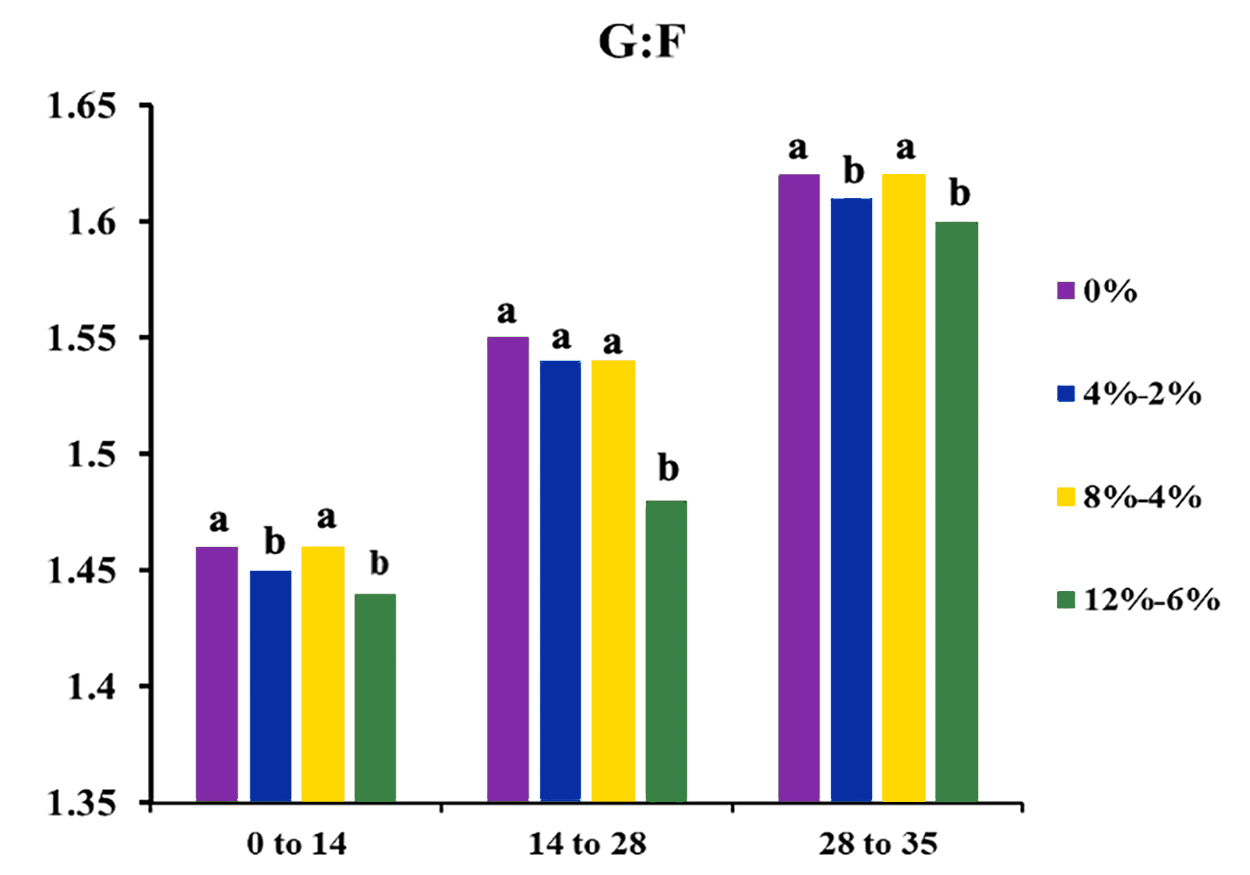

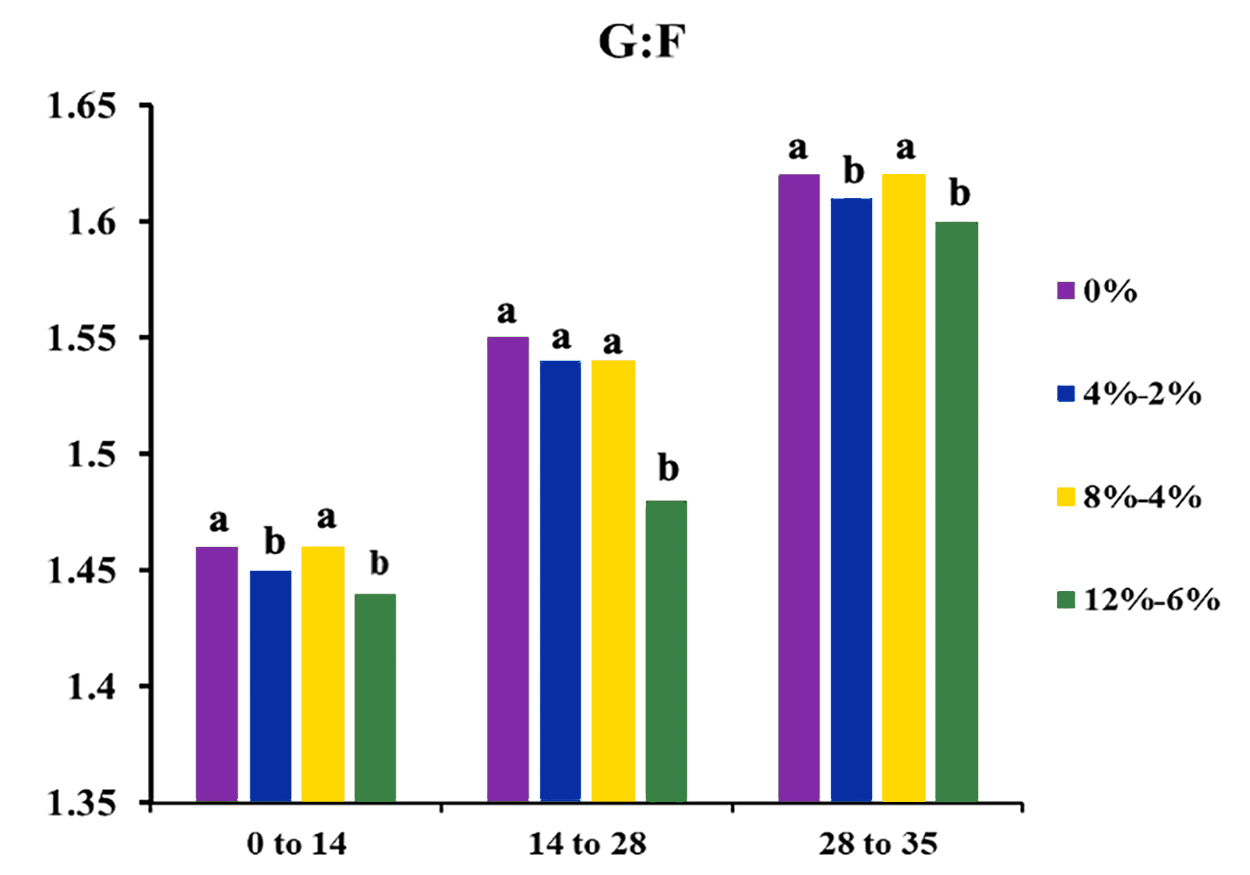

Results showed that average daily gain (abbreviated as ADG) responded similarly for the 0%, 4%, and 8% CFP diets during Phase 1; however, pigs fed 12% inclusion of CFP had a lower daily gain than the rest of the treatments (P<0.01; 0.33 versus 0.24 lbs/d). Pigs fed diets with 4% and 8% CFP in Phase 1 had a greater ADFI than pigs fed 12% CFP (0.42 versus 0.37 lbs/day; P˂0.01); 0% diets were intermediate (0.40 lbs/day). At the end of Phase 2, pigs fed 0%, 2%, and 4% CFP diets had greater G:F than pigs fed with 6% CFP inclusion (1.55; 1.54 versus. 1.48 P<0.01). No observed differences were measured between treatments for gut permeability.

Conclusion

Including CFP to replace soy protein concentrate did not impact the overall growth performance of nursery pigs compared to pigs fed with soy protein concentrate. However, although the 4% inclusion of CFP in Phase 1 improved feed intake, the highest inclusion of CFP in this trial negatively impacted growth performance at the same time. Considering that CFP generally prices lower than soy protein concentrate, replacing soy protein concentrate with CFP could help to reduce nursery pig feed costs without any negative impact on nursery pig growth performance.