Artificial insemination (AI) in swine is not a new technique. There are reports as early as the 1930s of collecting semen for insemination. However, use of AI in the United States has skyrocketed in the past decade. It is important to remember that AI is a tool that will work for your operation only if you are willing to manage and use it properly.

One of the disadvantages of AI is that it may require a higher level of management than some natural-service mating systems. For example, there is a greater chance of human error associated with AI than with natural service. When a boar naturally mates a sow, the semen is not subjected to severe changes in environment and is generally deposited into the female more than once during a period that spans the optimal time for fertilization. In contrast, many environmental changes are possible when semen is collected, diluted, transported and then deposited artificially. The inseminations must be done correctly and at the optimal times. To obtain a high conception rate and litter size, estrous detection (heat checking) must be done carefully and without fail.

Sanitation of the equipment as an important consideration in all AI procedures. Today it is possible to handle semen using all disposable materials, which alleviates the need for rigorous sanitation of equipment. When a conscientious effort is made to consider and incorporate these practices, AI can work on any operation.

Perhaps the greatest advantage of AI is that it permits you to make greater use of new, superior genetics at a potentially lower cost than some natural-service systems and with less risk of disease transmission. Purchasing semen allows genetic diversity, which can be used to optimize crossbreeding systems on smaller farms, and increased genetic progress. This can be achieved without the expense of purchasing and maintaining a single, superior boar. Additionally, good boars can be used more extensively than those used for natural service, because AI increases the number of inseminations per ejaculate.

Swine estrous cycle

The estrous cycle in the pig averages 21 days but can range from 17 to 25 days. The first day of standing heat, when the female is receptive to the male and will stand to be mounted, is referred to as day 0. The two or three days that the female is sexually receptive is termed estrus. The standing reflex is stimulated by contact with a mature boar. The boar’s submaxillary salivary glands produce pheromones that are secreted into the saliva. Direct physical contact is the best way to ensure that these stimulatory chemicals are transmitted to the female. The pheromones signal to the female that a mature boar is present and initiate the standing reflex if the female is in estrus. The female may or may not also exhibit other visible signs, including mounting or attempting to ride other females, a swollen, red vulva, mucus from the vulva, “popping” of the ears, and increased vocalization and activity. In gilts, estrus may last only a day or two, while a sow may be in estrus for three days. Although ovulation (release of the egg from the follicle on the ovary) usually occurs 23–48 hours after the onset of estrus, this event is extremely variable. In fact, a sow may ovulate before estrus occurs. It is for this reason that producers generally inseminate females more than once.

Detecting estrus

The importance of estrous detection in an AI system cannot be overemphasized. It is absolutely vital to the success of each breeding for the producer to be accurate in estimating the onset of estrus. Twice-daily estrous detection is more effective than once-daily detection, although it is also more time- and labor-consuming. The challenge with twice-daily estrous detection is that the benefits can be realized only if both checks are done properly and as close to 12 hours apart as possible. The frequency of estrous detection will determine the accuracy of estimating the onset of estrus. For greatest efficiency, estrous detection should be done first thing in the morning, before feeding or at least an hour after feeding. If this is not possible, the afternoon or early evening can work if the ambient temperature is not too high. The principle is to perform estrous detection when gilts and sows are not distracted or frustrated. Estrous detection should be conducted in a neutral pen with females in groups of 12 or less. By taking both the females and the boar to a novel pen, you will optimize the accuracy of estrous detection. This is an especially important aspect of estrous detection in gilts. With sows in gestation crates, a boar should be blocked in the aisle in front of four or five sows at a time for individual contact and to ensure that the technician is able to observe all sows for estrus before they become refractory. Pressure can be applied manually to the sow’s back while in the presence of the boar to determine estrus. The boar will generally chant, salivate and attempt to mount most of the females. A female in estrus may seek out the boar and will stand to be mounted. Once a female is detected as being in estrus, she should be removed from the pen so the boar will circulate to the other females.

It is critical to mate the female within a few hours before ovulation. However, timing of ovulation varies. Gilts will generally ovulate sooner after the onset of estrus than sows. There is also variation among farms, genetic lines and individual females. Because sows stand longer than gilts and because ovulation in both sows and gilts occurs near the end of esturs, it is recommended that with twice-daily heat checks, gilts be inseminated 12 hours after detection of estrus and sows be inseminated 24 hours after detection of estrus. With once-daily heat checks, the accuracy of estimating the onset of estrus decreases; therefore gilts and sows are usually bred when they are found in estrus. As patterns of expression and duration of estrus are established for a given farm it may be possible to refine the timing and number of inseminations. Additionally, it is recommended that all females be mated once daily each day they stand. While this potentially results in some waste of semen, it is the best way to ensure that at least one mating is optimally timed relative to ovulation.

The female reproductive system

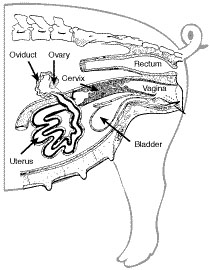

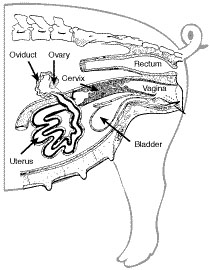

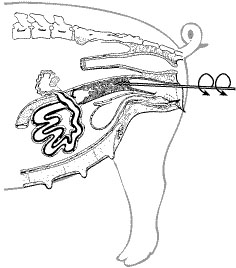

The reproductive system of female swine is more conducive to AI than that of cattle or sheep, and therefore AI is less time-consuming and easier to accomplish in swine. Still, the proper technique and an understanding of the system are important for best results. Figure 1 shows the reproductive organs of the female. The vulva is the visible portion of the female reproductive tract and may be red and swollen before or at the time of standing heat. The vulva leads to the vagina, which tapers into the cervix. The cervix consists of multiple ridges that act as a barrier to prevent bacteria, dirt and other foreign material from entering the uterus. During estrus, the cervix becomes swollen, which allows the AI spirette or catheter to be “locked” into it. (“Spirette” refers to a spiral-shaped, plastic-tipped insemination rod; “catheter” refers to a foam-tipped insemination rod.) This prevents some semen backflow and initiates uterine contractions, which are essential for sperm transport through the uterus to the oviduct, the site of fertilization. The ovary releases the eggs (oocytes) during ovulation and the oocytes enter the oviduct. In natural mating, the boar’s penis (which is corkscrew-shaped) fits into the folds of the cervix, and the pressure causes the penis to begin ejaculation. The semen travels through the uterus with the help of uterine contractions signaled by the presence of the penis in the cervical folds and into the oviduct, where it combines with the egg (fertilization). Freshly ejaculated sperm are not capable of penetrating an egg and must be present in the female reproductive tract for two to three hours to undergo the biological changes necessary for fertilization. This process is referred to as sperm capacitation.

Inseminating the female

- It is a good idea to evaluate semen with a microscope before using it (guidelines for evaluating semen are published elsewhere). Shipment, dilution, storage temperature, fluctuations in temperature and length of time since collection may all affect the shelf life, motility and viability of the semen.

- Before inseminating the female, use a paper towel to clean the vulva.

- Lubricate the tip of the spirette or catheter using any nonspermicidal lubricant or a few drops of extender. Take care to avoid getting lubricant in the opening of the spirette/catheter.

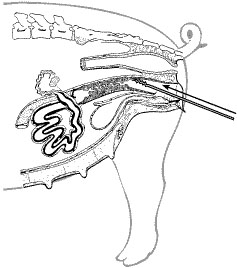

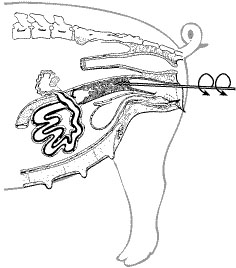

- Gently guide the spirette/catheter, with the tip pointed up, through the vagina to the cervix (Figure 2). The bottle of diluted semen is not attached to the spirette/catheter at this point. Keeping the tip of the spirette/catheter up minimizes the chance of coming in contact with the bladder, which could cause a backflow of urine into the spirette/catheter. If this happens, a new spirette/catheter is needed, because urine kills sperm. This is the primary reason the bottle of diluted semen should not be connected to the spirette/catheter until the cervix has been entered. Another reason is to avoid exposing the bottle unnecessarily to extremes of light or temperature. When using the cochette system instead of a bottle, it is common to attach the cochette first because of the dexterity required in doing so.

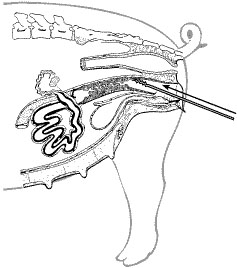

- When using a spirette, a counterclockwise rotation will insert the spirette into the cervix (Figure 3). At this time, resistance can be felt by gently pulling back on the spirette. When using a foam-tipped catheter, the catheter is not always inserted into the cervix. Instead, the catheter is positioned up against the cervix. However, some breeders push gently in an attempt to insert the foam tip into the first cervical ring. If the foam tip is securely locked in the cervix, resistance will be felt when the catheter is rotated.

- Gently invert the bottle of diluted semen two or three times to mix the semen. Attach the bottle to the end of the spirette and discharge the semen slowly. A gentle squeeze to start the process may be needed, but after that the semen should be allowed to be taken up by uterine contractions. This process will usually take at least three minutes. Because of the variation in intensity of uterine contractions, gilts will usually take longer to inseminate than sows. Depositing the semen too rapidly will cause a backflow of semen out of the vulva. Obviously, semen that flows out onto the ground is wasted. Remember that you are attempting to replace the boar, which spends five to ten minutes at each breeding.

- A small amount of backflow is expected. If an excessive amount of backflow occurs, stop. Either the semen is being deposited too rapidly (the semen needs to be deposited at a slower rate) or the spirette is not locked into the cervix. If semen flow stops, reposition the spirette by turning it a quarter of a turn (if you are using a foam-tipped catheter, move it gently back and forth) to reinitiate semen flow. Additionally, using sidecutters or a pocketknife to cut a hole in the semen bottle can be helpful if flow has stopped because of a vacuum buildup.

- If there is a great deal of resistance to the flow of semen, reposition the spirette, because the tip may be lodged against a cervical fold.

- Semen transport, and therefore fertilization, can be inefficient when females are frightened or disturbed; females should always be handled calmly and gently. The breeder is trying to mimic the boar, and greatest fertility occurs when this is done well. Having a boar present, applying some back pressure and massaging the female’s flank during insemination may increase the number or intensity of uterine contractions that draw semen from the bottle and transport it into the uterus. This is especially true in breeding gilts. If the female has been “locked down” and stands to be mounted for a long period of time, she may become refractory (that is, she may no be longer be able to stay in the “locked down” position). If this happens, simply remove the female from the boar’s presence for at least an hour and then try again. It is important that the female initiate the standing reflex while being inseminated; this elicits the uterine contractions that are vital for sperm transport.

- When all of the semen has been deposited into the female, remove the spirette by rotating it clockwise while gently pulling. Some people prefer to leave the catheter in place for several minutes to prolong cervical stimulation.

- A new spirette/catheter should be used for each insemination to eliminate the possibility of transmitting a disease or infection from one female to the next.

- Keep the female in quiet surroundings for 20–30 minutes. Distress at this time may still disrupt semen transport and fertilization.

References

- The Swine AI Book: A Field and Laboratory Technicians’ Guide to Artificial Insemination in Swine