Swine producers may be facing an emerging respiratory condition without really knowing about it.

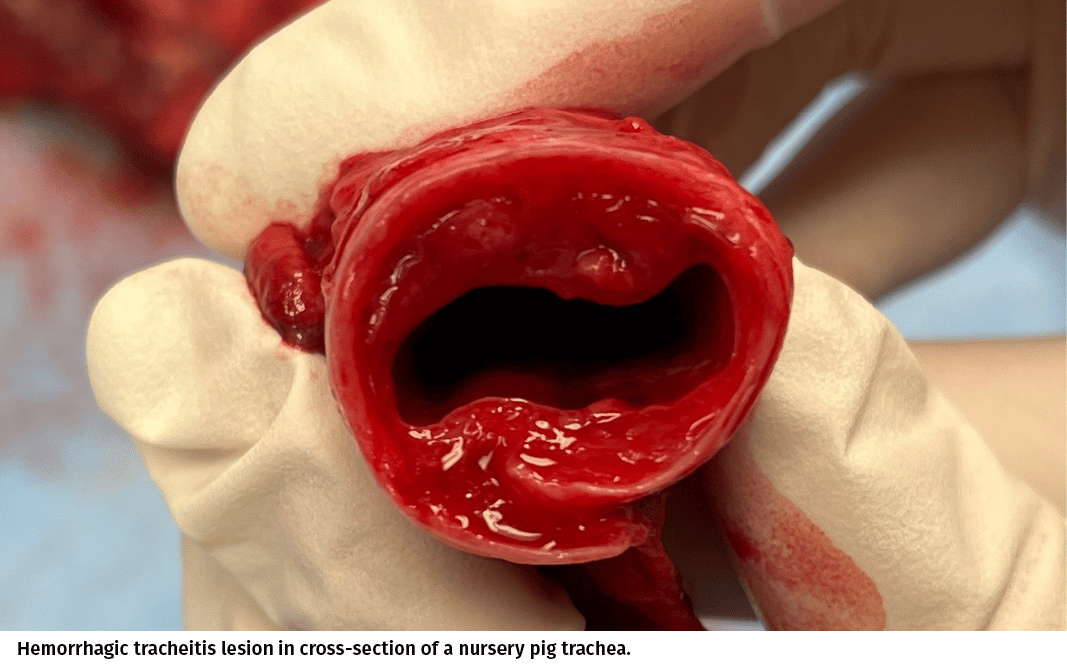

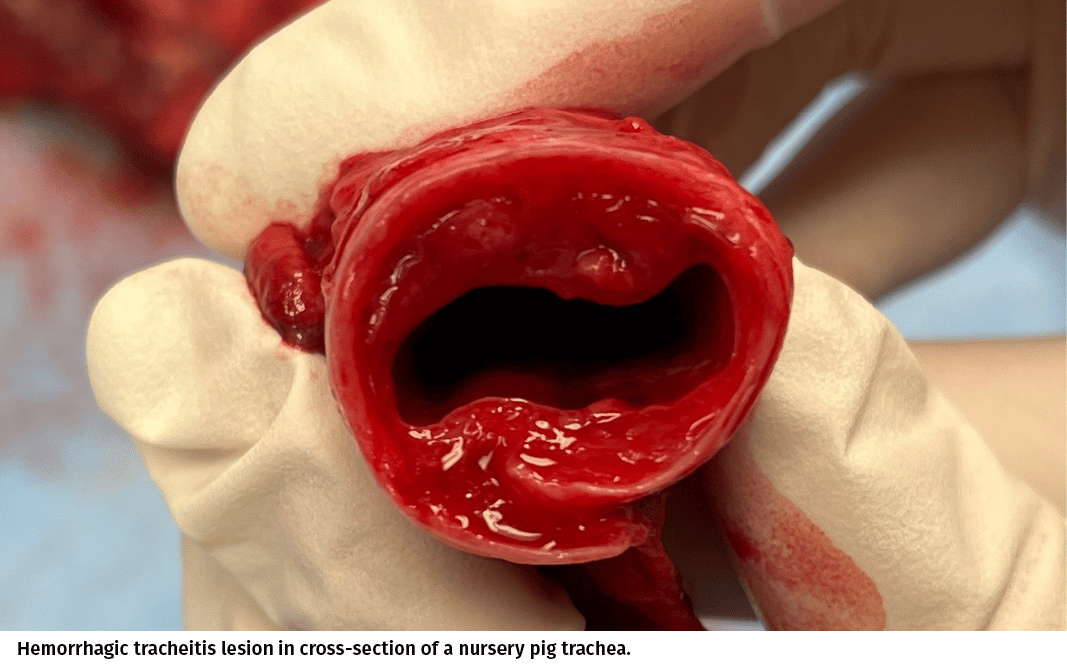

According to Dr. Michael Pierdon with Four-Star Veterinary Services in Pennsylvania, hemorrhagic tracheitis syndrome (HTS) is a clinical respiratory condition that has been identified in pigs that presents with a characteristic gross lesion on necropsy of hemorrhage in the trachea (windpipe) that becomes obstructive. The lesion causes severe coughing and, due to the restricted airway, high mortality.

The pigs develop a hemorrhage underneath the mucosa of the trachea, which creates a “blood blister, for lack of a better term,” that restricts the airway and causes issues with breathing, and ultimately, causes death, he said.

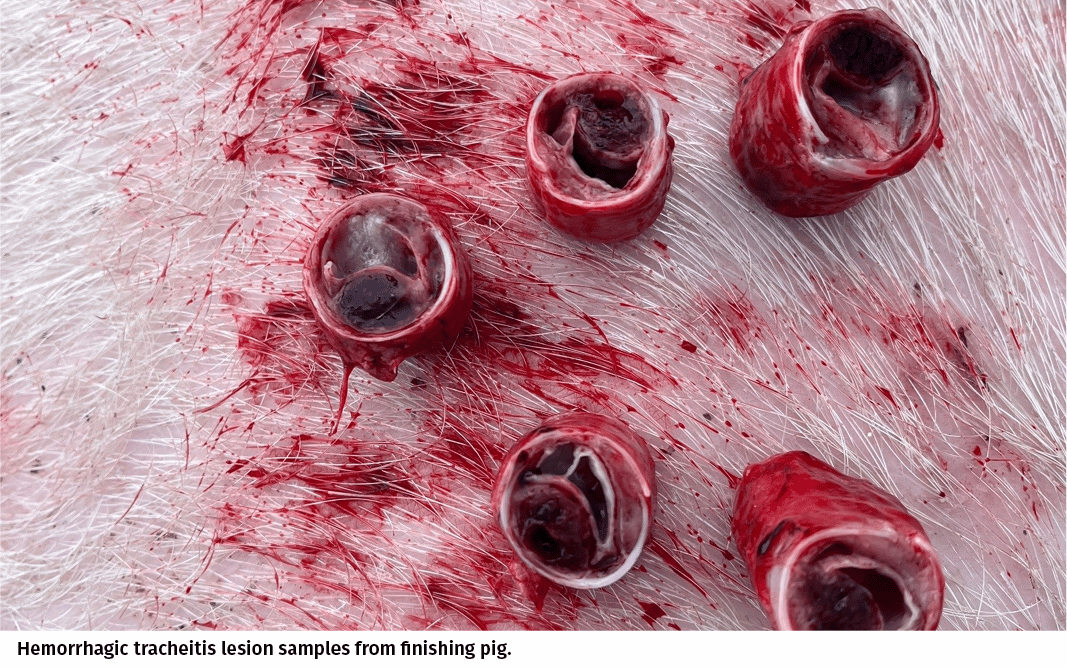

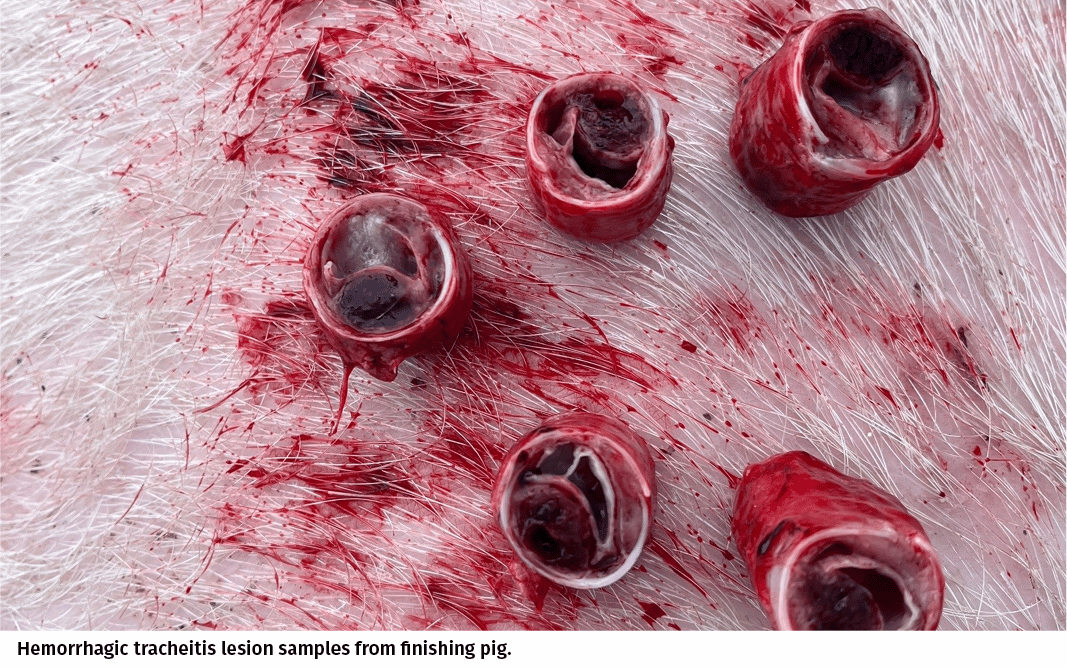

HTS primarily affects growing pigs, with the most dramatic outbreaks occurring in heavier finishing pigs, maybe 125-lbs plus, in Pierdon’s experience. He said he has diagnosed it in younger pigs, including in the nursery, although the severity of the gross lesion is less impressive in younger animals and the mortality doesn’t tend to be as high.

According to Pierdon, mortality rates are in the 1%–2% range. With a sudden acute outbreak of respiratory disease in mid- to late-finishing, with 1%–2% mortality over the course of a week, the losses can be substantial.

HTS is not new, he added, noting that the Swine Health Information Center held a webinar on it in 2020, but it hasn’t gotten a lot of attention because the trachea is not a tissue that is often examined or collected during a routine field necropsy.

The causative agent(s) are also yet to be determined, Pierdon said. “With respiratory conditions, people think lungs. What really put me on the trail of this is finding respiratory outbreaks with severe coughing and high mortality and sudden onset in mycoplasma-negative flows that we would oral-fluid test and find negative for PRRS and influenza.” he said.

While there are really severe lesions inside the trachea, the lungs often do not have significant lesions, he said.

HTS could easily look like influenza, and even that kind of mortality would be typical in an influenza outbreak in late-finishing pigs, Pierdon said, but it’s really telling when there are respiratory outbreaks that test negative for influenza, but those pigs still have those signs.

Clinical management

According to Pierdon, HTS outbreaks should be treated symptomatically with anti-inflammatories and sometime expectorants. He said antibiotic treatments are not particularly helpful given that there hasn’t been a consistent bacterial diagnosis associated with the condition and the affected animals tend to be heavy, market-ready hogs.

He added that it seems to be highly contagious within a barn with symptoms developing over a short period of time (24–72 hours), with the duration of clinical signs lasting 7 to 10 days.

With its rapid onset and lack of definitive cause, Pierdon said it is hard to get in front of the outbreak so it needs to run its course while supportive therapy is provided to clinically manage the pigs through the outbreak.

Critical actions

Pierdon’s goal is to raise awareness of this syndrome or clinical condition as a way of encouraging people to actually open the trachea and look for it. If a barn of pigs experienced an outbreak and oral-fluid samples tested positive for influenza, the assumption would be that it was an influenza case. Pierdon’s hypothesis is that it can’t just be him in Pennsylvania that is finding this problem and he wants other people to know to look at tracheas so those samples can be sent to the diagnostic labs. From there, the diagnosticians and epidemiologists can have more opportunity to try to figure out the actual cause of HTS. If it can be demonstrated that HTS is more common than believed, research funding may become available to further study and understand the problem better.

Pierdon said the lesions are most commonly found inside the trachea between the larynx and the thoracic inlet – in a market hog, about 4 in. behind the larynx. The lesions are most apparent when the trachea is cut in cross-section, he added.

He encouraged swine producers with pigs exhibiting acute and sudden outbreaks of coughing associated with mortality to have pigs necropsied, including an examination of the trachea. Producers can do this themselves or have a veterinarian investigate, but the point is to open the tracheas.

Veterinarians finding HTS lesions should include fresh and fixed pieces of trachea in their diagnostic tissue submissions to the diagnostic lab of their choice for gross diagnosis and histopathology.

By encouraging samples being submitted to diagnostic labs, Pierdon hopes a critical mass of confirmed cases will demonstrate the scope of the problem and make funding available to better understand HTS.