Every week a new Science Page from the Bob Morrison’s Swine Health Monitoring Project. The previous editions of the science page are available on our website.

In today’s Science Page the MSHMP team takes a look at Senecavirus A incidence in the United States over the past decade.

Key Points:

- Senecavirus A (SVA) incidence in U.S. breeding herds was estimated using diagnostic and outbreak data to characterize disease patterns.

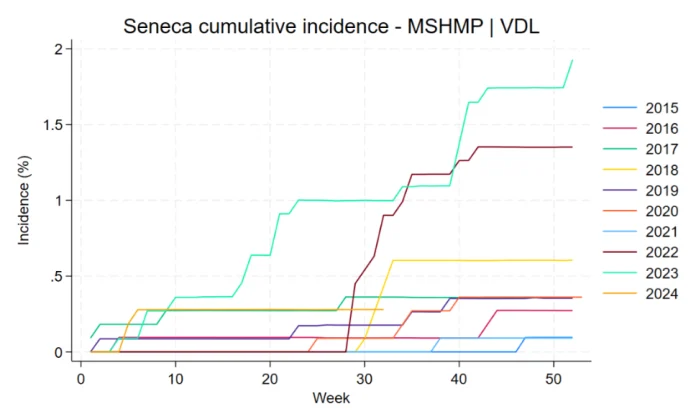

- From 2015 to 2024, the yearly SVA incidence in U.S. breeding herds ranged from 0.09% to 1.93%, peaking in 2023.

- SVA outbreaks primarily occur in the Midwest, peaking in the third and fourth quarters annually.

Introduction

Once clinical signs and lesions caused by Senecavirus A (SVA) are present, a foreign animal disease (FAD) investigation is needed to differentiate it from other vesicular diseases of concern (i.e., Foot-and-Mouth Disease). However, the data needed for a comprehensive understanding of its national occurrence in the U.S. are not readily available. Most reports of SVA occurrence rely on seroprevalence or case counts from submissions to Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratories (VDL). While informative, these may include environmental sampling or multiple submissions from the same outbreak, which can potentially lead to an overestimation of disease occurrence. Furthermore, since laboratory submissions are likely driven by clinical suspicion, the positivity rate might be higher than expected in the general population. Therefore, we aimed to estimate the breeding herd SVA cumulative incidence in the U.S. to better characterize the disease burden and begin outlining prevention and control measures.

Methods

The diagnostic data analyzed in this study were provided by the University of Minnesota and Iowa State University VDL’s from January 2015 to May 2024 and originated from the progressive group of MSHMP participants which today represent approximately 60% of the U.S. breeding herd. Data regarding all SVA PCR submissions during the period included specimen submitted and Premises IDs. We excluded environmental samples, isolates, and miscellaneous specimens from the incidence estimations. Positive submissions from the same site that were submitted within nine weeks apart were considered to be representative of the same outbreak, and thus not counted as a new case (Preis et al., 2024). An outbreak was also considered if no positive submission was detected but the site directly reported an SVA outbreak to MSHMP, as the site may have used other VDLs for detection. Yearly cumulative incidence was calculated using the number of breeding herds reporting statuses to MSHMP for either PRRS, PED, or SVA (i.e., sites sharing information for at least one of the primary diseases monitored by MSHMP) as the denominator, and the number of positive SVA submissions/reported as the numerator.

Results

From 2015 to May 2024, 63 SVA breeding herd outbreaks were detected in 55 sites from 13 production systems across 12 states. Five sites experienced two SVA outbreaks each, while three sites had three SVA outbreaks during the study period. For sites that experienced multiple outbreaks, the median time interval between SVA outbreaks was 98 days (interquartile range: 80.5 – 147 days). Most outbreaks occurred in the third and fourth quarters of the calendar year (28 and 14 outbreaks, respectively) followed by the first and second quarters (12 and 9 outbreaks, respectively). The majority of outbreaks detected, originated in the Midwest (82.54%), followed by the South (12.70%) and the Northeast (4.76%). The yearly cumulative incidence ranged from 0.09% in 2015 and 2021 to 1.93% in 2023 (Figure 1).

Discussion

The first ever U.S. breeding herd SVA cumulative incidence metric highlights epidemiologic characteristics of the virus. Temporal patterns indicate a higher frequency of outbreaks in the third and fourth quarters of the year, suggesting possible seasonal effects. Yearly variability in incidence rates may reflect differences in surveillance, reporting, transport sanitation efficacy protocols, or actual disease fluctuations. The higher incidence in recent years may suggest either an increase in the true prevalence of SVA or improvements in detection and reporting mechanisms. Enhanced surveillance systems that integrate on-farm observations and other diagnostic tools could provide a more accurate picture of SVA dynamics, which is crucial for developing more effective control measures.

ReferencePreis et al., 2024. First assessment of weeks-to-negative processing fluids in breeding herds after a Senecavirus A outbreak. DOI: 10.1186/s40813-023-00353-7