Fitting diets to your farm

You can optimize nutrition on your farm by modifying your feeding program specific to your farm. Accurately determining and meeting pigs’ nutrient requirements is key to better feeding. A pigs’ nutrient requirements depend on many factors. Thus, one diet can’t meet the needs of all pigs in different swine operations.

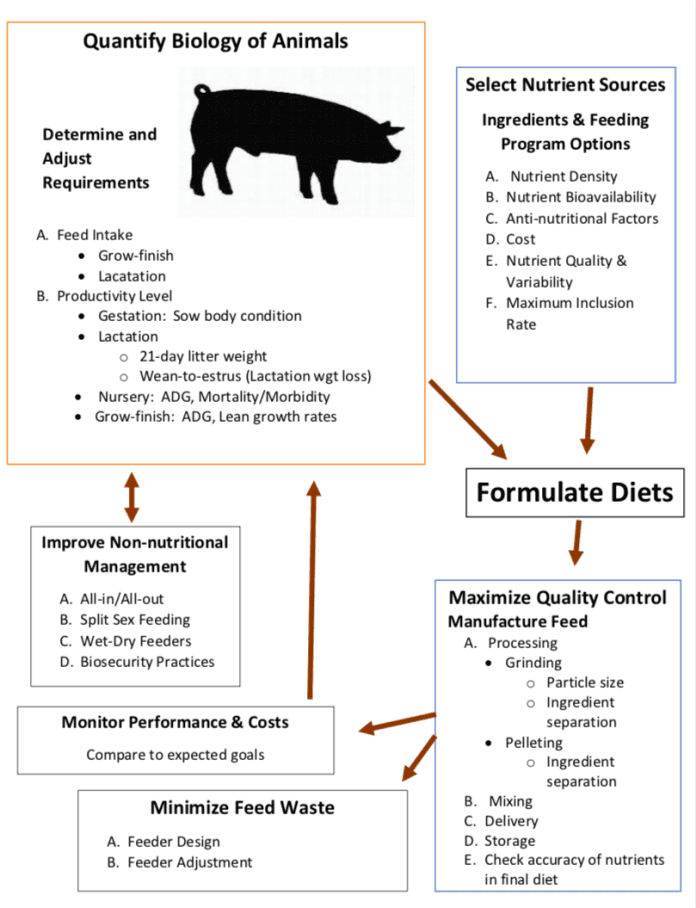

The following image outlines the steps for developing and managing swine nutrition programs. As you follow each step, assess the current economic conditions and resources available to you.

|

The National Research Council’s (NRC) Nutrient Requirements for Swine lists the amount of dietary nutrients pigs require to meet specific:

- Growth weights.

- Feed conversions.

- Reproductive levels.

These requirements apply to pigs fed corn-soybean meal diets under ideal conditions. You should consider the NRC’s nutrient requirement recommendations as the minimum levels needed.

Feed industry representatives recommend nutrient levels that are nutrient allowances. Nutrient allowances have a “margin of safety” over NRC levels. This article aims to make sure nutrient levels are adequate, economical and can be tailored to specific conditions.

The two ways to express nutrient allowances include:

- Amount of nutrient per day.

- Nutrient content in the diet.

Daily nutrient allowances

- Usually stays the same.

- Relate to the pig’s nutrient needs to maintain its body and nutrient needs for productive functions.

For example, a sow producing 16 pounds of milk daily requires about 19.4 mega calories of metabolizable energy (ME) daily. This energy need stays relatively the same whether she eats 8 or 18 pounds of feed.

Concentration nutrient allowances

- Depends on the amount of feed eaten.

Consider the example sow eating a corn-soybean diet containing 1.47 mega calories of ME per pound. She needs 19.4 mega calories of ME daily.

Daily nutrient intake = Nutrient content of diet x Daily feed intake

If she eats 13.2 pounds of feed daily, her energy needs will be met:

Daily nutrient intake = 1.47 Mcal/lb of feed x 13.2 lbs/day = 19.4 Mcal ME/day

If she eats 10 pounds of feed daily, she won’t meet her energy needs:

Daily nutrient intake = 1.47 Mcal ME/lb of feed x 10 lbs feed/day = 14.7 Mcal ME/day

Set goals specific to your farm. You may divide your goals among performance, cost and production scheduling (barn throughput).

Performance goals

Greater efficiency and profitability can often improve performance. You may set performance goals for lean gain per day, feed conversions, 21-day litter weight, etc. Consider the following when making performance goals.

- What is the current level of performance in your herd?

- Can and should a higher level of performance be reached?

- Will improving nutrition increase performance?

- If so, what parts of your nutrition program can you change to improve performance?

- Will adjusting your feeding program improve profitability?

Production and cost goals

Facility and diet costs make up part of the total production cost. With high facility costs, you may choose an expensive feeding program that supports rapid growth and reduces the fixed cost per pig. This plan may reduce total production cost. With low facility costs, you may choose a less expensive diet that slows gains, but lowers total production cost.

Factors that influence nutrient needs

|

Pigs have daily nutrient needs to maintain their bodies and support productive functions. Underfeeding nutrients results in poorer performance. But overfeeding nutrients can increase feed costs. Measure feed intake to determine the amount of nutrients your pigs consume. You can calculate feed intake by:

Feed intake = Total feed eaten÷(Number of pigs x Number of days)

Once you know the feed intake, adjust the dietary nutrient content to make sure your pigs meet their needs. You can calculate nutrient intake by:

Nutrient intake = Nutrient content of diet x Daily feed intake

For example, if a 60-pound barrow requires 20.0 grams of lysine daily and eats 3.5 pounds of a diet that contains 0.9 percent lysine, he would only get 14.3 grams of lysine daily.

Daily lysine intake = 3.5 lbs feed/day x (0.9 lysine÷100) x 454 g/lb = 14.3 g lysine/day

If the pig consumes 5.5 pounds of this feed he would get 22.5 grams of lysine daily.

More information on methods to determine feed intake at each production phase are below. These methods measure “feed disappearance” as feed waste can increase estimates of feed intake. Thus, good feeder design and care are important.

Performance level affects a pig’s nutrient requirements.

- A sow raising 12 pigs will produce more milk and thus require more nutrients than a similar sow raising eight pigs.

- A pig gaining 0.75 pounds of lean tissue daily requires more nutrients than one gaining 0.6 pounds of lean tissue daily.

You can measure the productivity of your swine herd on a given farm under specific conditions. But potential performance level is usually unknown. Set nutrient levels slightly above those that support current performance levels. As you feed new diets, measure performance levels. If performance improves, adjust nutrient levels steadily upward until you achieve optimal performance.

Factors impacting feed intake and productivity level include:

- Genetics.

- Season.

- Age or growth stage.

- Health status.

- Feed form.

- Feed palatability.

If any of these factors change, measure the feed intake so you can adjust the diet to meet your pigs’ nutrient needs.

Water intake

Water is the most important nutrient for the pig. Water makes up about 80 percent of the pig’s body at birth and 50 percent of the market hog’s body.

A pig housed in thermoneutral conditions will consume 2 to 3 pounds of water for every pound of dry feed eaten. Under heat stress or during lactation this may increase to 4 or 5 pounds of water for every pound of feed. Water intake also changes between different classes of pigs (see table 1).

Table 1. Estimated Water Intake of Pigs (National Swine Nutrition Guide, 2010)

| Class of pig | Water intake (gal/head/day) |

|---|---|

| Sow and litter | 6.5 – 11.0 |

| Nursery pig | 1.0 |

| Growing pig | 2.5 – 3.0 |

| Finishing pig | 4.5 |

| Gestating sow | 2.5 – 6.0 |

| Boar | 8.0 |

Water quality

Water quality guidelines for pigs (see table 2) are similar to, but more relaxed than the standards for humans. Regular water quality monitoring is important. At a minimum, the water should be tested annually and should always include a coliform bacteria test.

Table 2. Water quality guidelines for swine (Adapted from M. Shannon, 2011)

| Water analysis | Acceptable range |

|---|---|

| pH | 6.5 – 8.0 |

| Total dissolved solids (TDS) | 0 – 3000 ppma |

| Nitrate nitrogen | 0 – 100 ppm |

| Nitrite nitrogen | 0 – 10 ppm |

| Sulfate | 0 – 1000 ppm |

| Chloride | 0 – 500 ppm |

| Iron | 0.0 – 0.3 ppm |

| Sodium | 0 – 150 ppm |

| Total bacteria | 0 – 1000/ml |

| Coliform bacteria | 0 – 50/ml |

aTotal dissolved solid levels up to 5000 ppm can be tolerated with some adaptation.

Estimating nutrient needs at each production stage

|

Feeding goal: to control weight gain and body condition while supporting fetal growth.

Limit-feed sows to prevent excessive weight gain.

Measuring feed intake for gestating sows

Scoop method

- Fill a scoop to a chosen level.

- Weigh the contents of the scoop and record the weight.

- Repeat this procedure several times to find the average amount of feed the scoop will hold.

- Count and record the number of scoops given to each animal at feeding.

- Periodically re-check the weight of feed the scoop will hold.

- Feed density changes reduce the accuracy of this method.

- Check the measure of automatic feed drop systems.

Producers commonly feed sows a gestation diet at about 4 to 6 pounds daily. This amount of daily feed is only a target and the actual amount fed will differ between each animal and case. Reducing daily feed allowance to less than 3 pounds per head may cause inadequate intake of vitamins and minerals with typical gestation diets.

Factors affecting gestating sow diets

Size of sow

Larger, heavier animals have higher maintenance requirements than smaller, lighter animals. Energy needs increase about 200 kilocalories ME for each 20-pound increase in body weight.

Housing and feeding

Breeding stock housed and fed in groups require about 15 percent more feed than individually fed animals. Timid sows won’t consume their full share of feed.

Temperature

Lower critical temperature (LCT) is the temperature at which below an animal needs additional energy to keep warm. Thus, sows housed at temperatures below their LCT need more feed to stay warm than sows housed in a warm setting. Increase feed allowances 1 pound for every 20 F below 60 F. This practice applies to the temperature sensed by the animal, which isn’t necessarily the same as the thermometer reading.

Body condition

Thin animals have less fat and require more feed when housed in lower temperatures than animals in good body condition.

Poor body condition in sows causes:

- Increased culling rate.

- Increased numbers of gilts in the sow herd.

- Decreased pigs and sows per year.

Overfat sows are more likely to experience:

- Increased embryonic mortality.

- Increased farrowing difficulty.

- More crushed pigs.

- Decreased feed intake during lactation.

- Lower milk production.

- Increased susceptibility to heat stress.

Thin sows may exhibit:

- Failure to return to estrus.

- Lower conception rates.

- Smaller subsequent litter sizes.

- Downer sow syndrome (broken bones and spinal injuries due to minerals moving from bones).

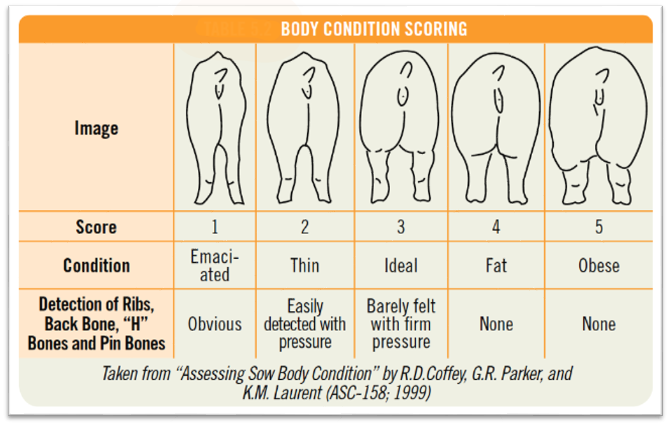

Evaluating a gestation feeding program

Condition scoring

This method combines visual exam and estimated backfat to score a number between 1 and 5. The desirable condition score at farrowing is 3. Adjust daily feed if the average score is above or below 3.

Younger sows and fatter genotypes may have more last-rib backfat.

Last-rib backfat for mature sows of lean genotype

| Condition score | Backfat (in) |

|---|---|

| 1 | Less than 0.6 |

| 2 | 0.6 – 0.7 |

| 3 | 0.7 – 0.8 |

| 4 | 0.8 – 0.9 |

| 5 | Greater than 0.9 |

Weigh animals

Weight gains depend on environmental conditions, genetics and the amount of weight lost during the previous lactation. The following are approximate weight gains during gestation, 114 days.

- Parity one: 80 to 100 pounds

- Parity two to five: 80 to 90 pounds

- Parity greater than five: 55 pounds

Providing enough nutrients for gestating sows

To achieve a good body condition score and weight gain, gestating sows need the following amounts of nutrients daily.

Metabolizable energy (ME): 6000 to 8000 kilocalories

Crude protein: 240 to 260 grams

Lysine: 8 to 13 grams

Calcium: 18 to 20 grams

Phosphorus: 16 to 18 grams

Feeding 4.5 pounds daily of a normal corn-soybean meal diet will meet these nutrient needs. You may need to adjust the feeding level to achieve your desired weight gain or body condition. Table 3 shows an example corn-soybean meal diet for gestating sows.

Table 3. Example of a diet for gestating sows

| Ingredients | Amount (lb) |

|---|---|

| Corn (0.25%) | 1,655 |

| Soybean meal, 44% | 260 |

| Dicalcium phosphate (18.5% P; 21% Ca) | 52 |

| Limestone (39% Ca) | 15 |

| Salt | 10 |

| Vitamin premixa | 6 |

| Trace mineral premixa | 2 |

| Total | 2000 |

| Calculated analysis | |

| ME, kcal/lb | 1,430 |

| Protein, % | 13.0 |

| Lysine, % | 0.55 |

| Calcium, % | 0.91 |

| Phosphorous, % | 0.80 |

aSee Table 10 for vitamin and trace mineral levels.

Calculating daily nutrient intake

Nutrient intake = Nutrient content of the diet x Daily feed intake

The following examples show the daily energy and lysine intake when feeding 4.5 pounds of the example gestation diet.

Metabolizable energy (ME) daily intake

Daily ME intake = ME kcal/lb of feed x daily feed intake

Daily ME intake = 1,430 kcal ME/lb of feed x 4.5 lbs feed/day = 6,435 kcal ME/day

Lysine daily intake

Daily lysine intake = (% lysine/lb of feed ÷100) x g/lb× daily feed intake

Daily lysine intake = 4.5 lbs feed/day ×(0.55 lysine ÷100) x 454 g/lb = 11.2 g lysine/day

Table 4 shows daily nutrient intake at different feed allowances of the example gestation diet. Four pounds per day of the example diet doesn’t meet the gestating sow’s daily needs for calcium and phosphorus.

- Increase the nutrient content of feed if sows are eating less than 4.5 pounds of feed daily.

- Decrease nutrient content if sows eat more than 4.5 to 5.0 pounds per day.

- You may decrease nutrient content to control over-feeding daily nutrients.

Table 4. Nutrients eaten daily at different intakes of example diet for gestating sows

| Nutrient | Feed allowance/day (lbs) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.0 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 5.5 | 6.0 | |

| ME Energy (kcal) | 5,720 | 6,435 | 7,150 | 7,865 | 8,580 |

| Protein (g) | 236 | 266 | 295 | 325 | 354 |

| Lysine (g) | 10.0 | 11.2 | 12.5 | 13.7 | 15.0 |

| Calcium (g) | 16.5 | 18.6 | 20.6 | 22.7 | 24.8 |

| Phosphorus (g) | 14.5 | 16.3 | 18.2 | 20.0 | 21.8 |

The example diet is meant for limit-feeding sows.

- Limit-feed by feeding in small groups.

- Use gestation or feeding stalls or computerized feeding stations.

- Don’t use synthetic lysine during pregnancy if you feed sows once daily.

- Under this care plan, synthetic lysine use is less efficient than lysine from natural protein in common feed ingredients.

- Lysine efficiency for full-fed sows shows no difference between synthetic and natural.

Alternative feeds

You can use alternative feeds to replace part or all of the corn and soybean meal with without harming performance. These feeds may partly or completely replace corn and soybean meal as energy and protein sources. Alternative feeds include:

- Alfalfa

- Barley

- Sorghum

- Canola meal

- Meat and bone meal

- Others

Consider the following when choosing an alternative feed:

- Cost.

- Nutrient content.

- Ingredient uniformity, does the feed change between purchases?

- Ingredient quality.

- Palatability, will the sows eat it?

- Geographic availability, can you easily purchase the feed in your area?

- Nutrient availability, can the sows easily use the nutrients in the feed?

- Presence of toxic or antinutritional factors, could the feed have mold, dirt, etc.?

More information on alternative feeds is available in Pork Industry Handbook factsheets:

Feeding goal: to control weight gain and body condition while supporting optimal breeding performance.

To control weight gain, limit-feed mature boars after reaching a body weight of 240 pounds. Overfeeding boars can cause reduced libido and large size, which is unsuitable with mating small females.

Measuring feed intake for mature boars

Measure feed intake by using the scoop method discussed for gestating sows. Producers commonly feed their sow gestation diet to boars at 5 to 6.5 pounds daily under most conditions. You should adjust this target to fit the needs of individual animals. Factors affecting each animal include:

- Size of boar.

- Housing method.

- Feeding method.

- Environmental temperature.

- Body condition.

Feeding boars a sow gestation diet

Research suggests feeding boars a sow gestation diet may not optimize reproductive performance. Limit-feeding the gestation diet to control weight gain:

- Limits protein intake.

- Decreases libido.

- Decreases semen production.

Mature boars need about 6,000 kilocalories of metabolizable energy and 17 grams of lysine daily to control weight gain and optimize reproductive performance. Feeding 4.5 pounds of the example gestation diet daily (table 3) provides 6,400 kilocalories of metabolizable energy, but only 11.5 grams of lysine. Thus, you should formulate a boar diet with 0.85 percent lysine.

Feeding boars a sow lactation diet

It may not be feasible to plan and handle a special diet for boars in smaller herds. Instead, you can limit-feed a sow lactation diet to breeding boars.

- Protein and lysine in lactation diets are higher than gestation diets.

- The energy content of the two diets are similar if the lactation diet doesn’t have added fat.

- Limit-feeding a lactation diet will control weight gain and provide more protein.

- Formulate a separate boar diet If the lactation diet contains more than 1 percent added fat.

Breeding load affects feed intake

Boars less than one year of age may need more feed than older boars because they’re still growing. You may need to increase feed intake to maintain body condition when heavily using boars.

Feeding goal: to minimize poor nutrient balance while optimizing milk production.

Lactating sows produce 15 to 25 pounds of milk daily and need three times more nutrients than gestation sows. The amount of milk a sow produces and the growth of nursing piglets affects the level of nutrient intake during lactation. Highly productive sows use nutrients from their bodies and feed to support lactation. This results in loss of body weight (negative nutrient balance). Excessive body weight loss can lead to:

Short-term reproductive problems

- Longer weaning-to-estrus periods.

- Smaller litter size in following seasons.

Long-term problems

- High culling rate of the sow herd.

- Low average parity.

- Reduced pigs weaned per reproductive lifetime.

- Higher genetic cost per pig produced.

Minimizing negative nutrient balance

- Increase feed intake or nutrient content in the diet.

- Determine the feed intake in gestation and lactation.

This method will:

- Reveal if sows aren’t eating enough.

- Provide a base level of intake and allow you to compare future intakes.

- Provide nutritionists with information to accurately plan sow diets for a specific herd.

Measuring feed intake for lactating sows

Scoop method

Measure feed intake by using the scoop method discussed for gestating sows. Record the amount the sows eat on a feed intake card.

Container method

- Weigh a bag or other large container of feed and record the weight.

- Place this container near the stall and feed the sow from this container only.

- When the container is empty, repeat the process until the end of lactation.

- At weaning, weigh the feed remaining in the container and feeder and subtract it from the total amount of feed offered.

- Divide this amount by the number of days of lactation for each sow.

Feed intake = total feed eaten / lactation length (days)

Nutrient intake

Calculating nutrient intake

Nutrient intake = Nutrient content of diet×Daily feed intake

Example:

A sow consuming 11 pounds of a lactation diet with 1,450 kilocalories of ME per pound would get 15,950 kilocalories of ME daily.

Nutrient intake = 1,450 kcal/lb of feed×11 lbs feed/day = 15,950 kcal ME/day

Assessing sow milk production

Make nutrient intake goals based on the sow’s level of milk production. Measuring average daily weight gain of the litter is the easiest way to assess milk production.

Avg. daily litter weight gain = (Litter weaning weight – Birth weight of live pigs)÷Lactation length (days)

Use table 5 to compare target nutrient intakes to the actual nutrient intake of each sow. You will need the average daily litter weight gain and sow body weight. For example, a 400-pound sow with a litter gaining 4.0 pounds daily has a target daily intake of 19.36 megacalories of ME and 46 grams of lysine.

Table 5. Energy, protein and lysine intake for lactating sows by level of production (Adapted from Pettigrew, 1993)

| Sow Body Weight (lb) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | 400 | 500 | |||||||

| Litter Gain (lb/d) | Energy (Mcal ME/d) | Protein (g/d) | Lysine (g/d) | Energy (Mcal ME/d) | Protein (g/d) | Lysine (g/d) | Energy (Mcal ME/d) | Protein (g/d) | Lysine (g/d) |

| 3.0 | 14.82 | 592 | 33 | 15.88 | 621 | 34 | 16.87 | 648 | 34 |

| 3.5 | 16.56 | 681 | 39 | 17.62 | 710 | 40 | 18.61 | 737 | 40 |

| 4.0 | 18.30 | 770 | 45 | 19.36 | 799 | 46 | 20.35 | 826 | 46 |

| 4.5 | 20.04 | 860 | 51 | 21.10 | 889 | 52 | 22.09 | 916 | 52 |

| 5.0 | 21.78 | 949 | 57 | 22.84 | 978 | 57 | 23.83 | 1,005 | 58 |

| 5.5 | 23.52 | 1,038 | 63 | 24.58 | 1,067 | 63 | 25.57 | 1,094 | 64 |

| 6.0 | 25.25 | 1,127 | 69 | 26.31 | 1,156 | 69 | 27.30 | 1,183 | 70 |

The nutrient intakes in table 5 try to account for lysine and protein from breakdown of body tissue. Sows may provide 4 grams of lysine and 61 grams of protein daily from body tissue during lactation. Table 5 doesn’t consider the energy given off from this process. Thus, the daily energy needs in table 5 assume zero weight loss and may seem higher than what sows need for commercial production. View these values as goals not requirements.

Maximizing nutrient intake

- Don’t overfeed during gestation.

- Feed two or three times daily.

- Make sure sows have water access.

- Keep farrowing room temperature between 65 and 70 F.

- Use drip or snout coolers to lessen summer heat stress.

- Remove spoiled or moldy feed.

- Make sure feeder design doesn’t limit feeding.

Deciding if you need to increase nutrient content in the diet

After maximizing feed intake, compare actual nutrient intakes with target intakes in table 5.

Sows producing a lot of milk may be unable to eat the amount of feed they need to get enough nutrients. Body weight loss (greater than 40 pounds) and low milk production may occur. Increasing the nutrient content of the diet may help offset these effects.

Use the following equations to calculate the proper nutrient content of the diet.

Nutrient Concentration = Desired Nutrient Intake ÷Feed Intake

Percent of the Diet = Nutrient Concentration ×100

Effects of adding fat to lactation diets:

- Increases energy intake of sows.

- May reduce weight loss and back fat loss.

- May increase daily gain of nursing piglets.

- Increases diet cost.

- Addition of fat above 5 percent:

- Increases the risk of feed becoming rancid without a preservative.

- Causes bridging and caking of feed in feeders and bulk bins.

More information on adding fat to lactation diets is available in the Pork Industry Handbook factsheet 3, “Dietary Energy for Swine” and Chapter 7 in Swine Nutrition by E.R. Miller, D.E. Ullrey and A.J. Lewis.

Providing a high nutrient diet

Highly productive sows need feed ingredients high in energy and protein such as corn and soybean meal. Feeds high in moisture or fiber may reduce the nutrient content and limit nutrient intake. These feeds include:

- Beet pulp

- Alfalfa hay

- Oats

- Wheat bran

Feeding goal: to optimize growth performance during the first few weeks after weaning.

Weaning young pigs (10 to 21 days old) can result in problems after weaning including:

- Decrease in gains.

- Low feed intake.

- Increase in sickness.

- Increase in death.

Factors affecting weaning success

- Environment: temperature, air quality, pen and equipment features.

- Health.

- Care practices.

- Nutrition.

Environment is the most important factor. After providing a good environment, nutrition is the next most important factor.

Changing from liquid milk to a dry starter diet

Along with other stressors at weaning, changing from liquid sow’s milk to a dry starter diet is hard for young pig. Diets promoting good performance in early weaned pigs are made using information on the sow’s milk and on the pig’s ability to use nutrients from commonly available feedstuffs. Dried milk products contain forms of protein (casein) and energy (lactose) that are highly digestible by the young pig.

Soybean meal

Pigs weaned at a young age (less than 21 days) are sensitive to anti-nutritional factors present in conventionally processed soybean meal. Thus, the level of soybean meal fed to these pigs should be limited. These young pigs develop an allergy to soybean proteins, which increases the incidence of diarrhea and reduces growth rate (postweaning lag).

After about two weeks, pigs become tolerant of soybean protein, the allergy slowly goes away and growth performance improves. Complex diets containing small amounts of soybean protein are fed to newly weaned pigs to avoid postweaning lag.

Feeding complex starter diets

Comparing complex to simple starter diets

Complex starter diets are high in:

- Dried milk products.

- Specially processed soybean products.

- Animal by-products: spray-dried pig plasma, spray-dried blood meal, fish meal.

- Highly digestible carbohydrates: oat groats.

Simple starter diets are made up of:

- Corn-soybean meal.

Feed ingredient quality

The quality of ingredients in complex starter diets greatly differ among suppliers. Only use high quality ingredients even though they’re more costly than lower quality ingredients. Contact a nutritionist for advice on feed ingredient quality for starter pig diets.

Effects of feeding a complex starter diet

Feeding complex starter diets to pigs weaned at less than 4 weeks of age greatly improves performance compared to simple diets. Some studies show complex starter diets high in milk products can improve performance during the grower and finisher phases of production.

As the pig grows, its digestive system can better use protein and energy from plant sources and becomes less sensitive to antinutritional factors. Thus, the performance boost gained by feeding complex diets instead of simple diets decreases over time. Furthermore, simple diets are considerably less expensive.

Phase feeding

Phase feeding is feeding several diets for a short period of time to more correctly and economically meet the pigs’ nutrient needs. Phase feeding better addresses changes in digestive capacity and feed intake after weaning.

Phase feeding programs for starter pigs provides a complex diet right away in the post-weaning period. As the pigs mature, you can gradually replace high-quality, expensive ingredients in these diets with less expensive, lower quality ingredients. Table 6 shows nutrient and ingredient suggestions for a phase feeding program. Example starter diets are shown in table 7.

Table 6. Nutrient levels and ingredients in phase feeding programs for starter pigs

| Item | SEWa | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weaning age | 2.5 weeks to 11 lb | 3 weeks 11 – 15 lb | 4 weeks 15 – 25 lb | 6 weeks or more 25 – 45 lb |

| Feeding period | About 1 week | About 1 week | About 2 weeks | About 3 weeks |

| Feed form | Pellet | Pellet | Pellet/Meal | Meal |

| Nutrient | % of the diet | |||

| Lysine | 1.70 | 1.50 | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| Methionine + cystine | 1.02 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| Ingredient | % of the diet | |||

| Dried skim milk | 0 – 20 | 0 – 10 | –––––– | –––––– |

| Dried whey | 15 – 30 | 10 – 20 | 10 – 20 | 0 – 10 |

| Fishmeal | 0 – 10 | 0 – 10 | 0 – 5 | –––––– |

| Special soy productsb | 0 – 20 | 0 – 20 | –––––– | –––––– |

| Spray-dried porcine plasma | 3 – 10 | 3 – 6 | –––––– | –––––– |

| Spray-dried blood meal | ––––– | ––––– | 2 – 5 | –––––– |

aSegregated early weaning.

bSoy protein concentrate, extruded soy protein concentrate or isolated soy protein.

Table 7. Example starter diets

| Ingredient | Lb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEW | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | |

| Corn | 734 | 927 | 1025 | 1120 |

| Soybean meal (44% CP) | 100 | 200 | 537 | 786 |

| Dried whole whey | 200 | 50 | –––– | –––– |

| Dried skim milk | 150 | 100 | –––– | –––– |

| Spray-dried pig plasma | 100 | 100 | 20a | 20 |

| Vegetable fat | 200 | 200 | –––– | –––– |

| Fish meal | –––– | –––– | 60 | –––– |

| Spray-dried blood meal | 3 | 10 | 34 | 37 |

| Dicalcium phosphate | –––– | –––– | 15 | 20 |

| Limestone | –––– | –––– | –––– | 8 |

| Salt | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Vitamin premixb | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Trace mineral premixb | 3 | 3 | –––– | –––– |

| DL methionine | 1.5 | 1.5 | –––– | –––– |

| L-lysine HCl | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Copper sulfate (25% Cu) | + | + | + | + |

| Antibiotic premixc | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 |

| Calculated analysis | ||||

| Crude protein | 24.00 | 21.60 | 21.00 | 22.20 |

| Lysine | 1.70 | 1.50 | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| Calcium | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Phosphorus | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

aIf Phase 2 diet is pelleted, increase fat to 80 lb at the expense of corn.

bSee Table 10 for suggested vitamin and trace mineral premixes.

cAdd at the expense of corn.

Segregated early weaning (SEW) diet

- Contains little corn and soybean (5 percent) meal.

- Contains a lot of highly digestible ingredients: dried skim milk, fish meal, dried whey and spray-dried porcine plasma.

- Forms pellets when you add high quality fat from plant sources (soybean oil, corn oil) at a rate of 3 percent.

- Helps promote growth if you add a sub-therapeutic level of antibiotic and copper sulfate.

Phase 1 diet

- You can use this diet for creep feeding and for small, runt or problem pigs weaned at older ages.

- Make sure this diet is in pellets to prevent clogging feeders and feeding systems.

- Ten percent soybean meal allows pigs to adjust to soybean protein.

Phase 2 diet

- Should contain 3 to 4 percent added fat.

- Should contain growth promoting levels of antibiotic and copper sulfate (125 ppm copper).

Pigs usually perform well on the SEW and Phase 1 diets, which tempts producers to feed it longer than a week. Avoid this practice to prevent pigs from eating large amounts of this expensive diet as they get older. Pigs will perform just as well on the Phase 2 diet at a less cost.

Measuring feed intake for starter pigs

Use the group or inventory method to measure feed intake. Make sure to account for frequent changes in the diet. “Feeding grower-finisher pigs” section discusses these methods further.

Seventy-five percent of total feed used in a farrow-finish operation is eaten in the grower-finisher phase. Thus, nutritional accuracy in this phase greatly impacts costs. Focus on defining amino acid requirements for grower-finisher pigs is important because:

- Amino acids impact lean growth.

- Amino acid sources add cost to the diet.

- Leaner pork is increasing in demand.

Genotype, sex and stage of growth may affect amino acid requirements. Making sure pigs get enough energy is equally important to optimize lean growth rate and efficiency.

Genotype

Research at Purdue University shows that lean growth potential differs greatly among genotypes.

Economic benefits for producing high lean growth genotype pigs:

- Faster growth rates.

- More efficient feed conversion.

- Increase in carcass leanness.

Differences in lean growth potential result in differences in amino acid requirements, especially lysine. Identifying the lean growth rates of pigs of different genotypes can help determine their protein and lysine requirements. The appendix shows a procedure to determine lean gain for pigs.

Sex

Differences between barrows and gilts

- Barrows eat more feed and grow faster.

- Gilts have less fat, more muscle, higher carcass yield, and better feed conversion than barrows at a similar weight.

- Gilts require more amino acids to promote optimal lean gain.

- When housed together diets are sometimes adjusted to partially meet both sex’s needs.

- Excess protein fed to barrows results in increased cost per pound of gain.

- Not enough protein results in reduced growth rate and decreased carcass lean in gilts.

Separating sexes to improve feeding

To effectively customize diets for barrows and gilts, you must pen and feed them separately. Separate sex feeding will usually increase profitability on lean value pricing if the cost of separating sexes is low. New swine facilities should be set up for separate sex feeding.

Differences in feed intake and carcass structure between sexes begin to appear above 40 pounds of body weight. The differences become greater as pigs reach market weight. Separate sexes when moving them into nursery or grower facilities.

Boars

Compared to gilts and barrows, boars:

- Gain faster.

- Are more efficient.

- Have less back fat.

- Need more amino acids.

Full-feed growing boars up to about 240 pounds to evaluate rate-of-gain and backfat depth for genetic selection programs. You can then limit-feed boars, see “Feeding mature boar” section.

Stage of growth

As body weight increases, the rate of muscle growth declines and maintenance needs increase. Thus, amino acid needs change with the stage of growth. Change lysine levels to match the changes in feed intake and nutrient needs along the pig’s growth curve. This change will improve the efficiency of amino acid use and can lower production cost.

The frequency of lysine level changes depend on knowing amino acid needs and the ability to handle multiple diets in your feeding system. Some producers have the information and flexibility to adjust diets every time they fill the feed bin. Those producers have a competitive advantage.

You must know growth rate and feed intake to fine-tune diets for grower-finisher pigs. Use the inventory or group method to record this information. The group method is more complex and provides more detailed information. When measuring growth rate and feed intake, randomly select pens to avoid location bias within the building. Count two pens sharing one feeder as one unit.

Measuring growth rate

Average daily gain (ADG) = [ (wt. out – wt. in) + wt. gain of pigs remaining in building] ÷ Pig-days*

*Pig-days = number of pigs × number of days of monitoring (inventory) period

Inventory method

- Requires producers to record:

- The weight of all pigs as they enter the building

- The number and weight of dead pigs

- The dates and weights of pigs marketed.

- Only provides an overall average ADG of all pigs over the entire inventory or grow-finish period in all-in all-out production.

- Doesn’t account for the gains of pigs in different stages of growth.

Group method

- Randomly select pens of same-aged pigs and weigh them at times throughout the grow-finish period.

- Identify and weigh pigs separately to provide accurate ADG.

- Monitor multiple pens of pigs to accurately determine a change in gain and intake.

Measuring feed intake

Measuring feed intake is a key to knowing protein and lysine levels in the grower-finisher phase. Minimizing feed waste is important because of the amount of feed eaten in this phase.

To calculate feed intake:

Average daily feed intake = (total lbs feed used) ÷ Pig-days

Inventory method

Record the weight of feed you give in the bin and subtract it from the amount remaining after inventory. Another way is to fill the bin and take inventory when the bin is full and when it’s almost empty. The inventory method doesn’t measure how much feed each pen of pigs ate.

Group method

The group method of measuring feed intake is more accurate. Producers select a representative number of pens and weigh the feed given in each feeder. After a period of time, they weigh the feed left in the feeder and subtract it from the total amount given. In some feeding systems, producers can detach and put the feeder on a scale.

Commercially available monitoring systems record feed intake using weigh hoppers or equipment measuring the amount of feed flow. You can set up bulk feed tanks with electronic load cells. By recording the weight of the tank after filling and at set time intervals, you can calculate the weight of feed eaten.

Lysine needs for grower-finisher pigs and developing boars

Table 8 shows estimates of lysine needs for grower-finisher pigs and developing boars.

For example, a 100-pound gilt of high lean growth genotype:

- She requires 23.0 g of lysine daily.

- If she consumes 3.0 pounds of grower feed daily, the feed should contain 1.69 percent lysine.

- If this gilt consumes 5.0 pounds of feed daily, the diet should contain 1.01 percent lysine.

These estimates were developed under ideal conditions and should be regarded as targets.

Table 8. Estimated dietary lysine needs for grower-finisher pigs and developing boars (Based on research at the University of Kentucky-Stahly, 1991 and Williams, 1984)

| Feed Intake (lb/day) | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lean Growth Genotype | Sex | Weight (lb) | Dietary Lysine (g/day) | Dietary lysine (%) | ||||

| High (>0.75 lb lean gain/day) | Mixed | 45 – 130 | 22.0 | 1.62 | 1.21 | 0.97 | 0.81 | –––– |

| 130 – 200 | 21.8 | 1.60 | 1.20 | 0.96 | 0.80 | 0.69 | ||

| 200–240 | 20.5 | –––– | 1.13 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.65 | ||

| Barrows | 45 – 130 | 21.0 | 1.54 | 1.16 | 0.93 | 0.77 | –––– | |

| 130 – 200 | 20.5 | 1.51 | 1.13 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.65 | ||

| 200 – 240 | 20.5 | –––– | 1.24 | 0.99 | 0.83 | 0.71 | ||

| Gilts | 45 – 130 | 23.0 | 1.69 | 1.27 | 1.01 | 0.85 | –––– | |

| 130 – 200 | 23.0 | 1.69 | 1.27 | 1.01 | 0.85 | 0.72 | ||

| 200 – 240 | 22.5 | –––– | 1.24 | 0.99 | 0.83 | 0.71 | ||

| Boars | 45 – 110 | 25.2 | 1.85 | 1.39 | 1.11 | 0.93 | –––– | |

| 110 – 175 | 24.6 | 1.81 | 1.36 | 1.08 | 0.90 | 0.77 | ||

| 175 – 240 | 24.6 | –––– | 1.36 | 1.08 | 0.90 | 0.77 | ||

| Medium (0.60 – 0.75 lb lean gain/day) | Mixed | 45 – 110 | 20.8 | 1.52 | 1.14 | 0.91 | 0.76 | –––– |

| 110 – 175 | 21.0 | 1.54 | 1.16 | 0.93 | 0.77 | 0.66 | ||

| 175 – 240 | 20.0 | –––– | 1.10 | 0.88 | 0.73 | 0.63 | ||

| Barrows | 45 – 110 | 20.0 | 1.47 | 1.10 | 0.88 | 0.73 | –––– | |

| 110 – 175 | 22.0 | 1.62 | 1.21 | 0.97 | 0.81 | 0.69 | ||

| 175 – 240 | 19.0 | –––– | 1.05 | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.60 | ||

| Gilts | 45 – 110 | 21.5 | 1.58 | 1.18 | 0.95 | 0.79 | –––– | |

| 110 – 175 | 22.0 | 1.62 | 1.21 | 0.97 | 0.81 | 0.69 | ||

| 175 – 240 | 21.0 | –––– | 1.16 | 0.93 | 0.77 | 0.66 | ||

| Boars | 45 – 110 | 24.0 | 1.76 | 1.32 | 1.06 | 0.88 | 0.76 | |

| 110 – 175 | 24.0 | 1.76 | 1.32 | 1.06 | 0.88 | 0.76 | ||

| 175 – 240 | 22.8 | –––– | 1.26 | 1.01 | 0.84 | 0.72 |

Formulating diets for grower-finisher pigs

- Measure feed intake and lean growth rate (see appendix).

- Conduct these measurements several time each year to account for seasonal differences in pig performance.

- Determine the nutrient needs for each type of pig.

- Lysine:

- Lysine is the first limiting amino acid in most pig diets. See table 8 for daily lysine needs.

- If you formulate the diet to meet the pigs’ lysine needs and use common feed ingredients, needs for other amino acids will also be met.

- Diets for high lean growth genotype may limit some amino acids if it uses synthetic amino acids. Consult a nutritionist to make sure amino acid ratios are good.

- Metabolizable energy:

- Cereal grain and soybean meal diets contain about 1,450 to 1,500 kilocalories of metabolizable energy per pound.

- Not enough energy usually limits growth rate in young growing pigs (up to 100 to 120 pounds depending on genotype).

- Maximize energy intake by making sure the diet is high in energy.

- Avoid feedstuff that lowers the energy less than 1,450 kilocalories of metabolizable energy per pound.

- Add fat to increase energy in the diet. Adding up to 5 percent of the diet usually

- Increases the growth rate.

- Lowers feed intake.

- Improves feed efficiency.

- Can increase backfat depth, especially during the finisher phase for low-to-average lean growth genotypes.

- Lysine:

- Formulate a diet based on feed intake that will meet the pig’s lysine needs.

- Use macrominerals, vitamins, and trace minerals following the guidelines in tables 9 and 10.

- You can add subtherapeutic levels of antibiotics if health condition allow it.

- Feed newly formulated diets and continue to monitor pig performance.

- Adjust the diet or management practices if desired pig performance isn’t achieved.

Vitamins and minerals are a small percentage of the diet, but they’re key to normal growth and productive functions. Vitamin lose their power when stored longer than three months or when exposed to:

- Minerals

- Heat

- Light

- Moisture

Limit storage time for basemixes and vitamin-trace mineral premixes by turning over inventory quickly.

Vitamin and mineral recommendations in this publication contain safety margins over NRC levels and are designed for use with good storage conditions.

Table 9 shows suggested macromineral levels and table 10 shows vitamin and trace mineral allowances. In practical cases, you can use the same vitamin and mineral premixes for breeding stock and starter pigs.

Table 9. Suggested macromineral level allowances

| Stage of Production | Calcium (% of diet) | Phosphorus (% of diet) | Salt (% of diet) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestation/Mature Boarsa | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.50 |

| Lactationb | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.50 |

| Starter | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.30 |

| Grower (45 – 100 lb) | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.40 |

| Finisher (100 – 240 lb) | 0.65 | 0.55 | 0.40 |

| Developing boars | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.40 |

| Replacement gilts (100 –240 lb) | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.40 |

aFeed intake > 4.5 lb/day.

bFeed intake > 11 lb/day.

In table 10, one number appears for each nutrient in each stage of production. This doesn’t mean that you can only supplement diets with this exact amount. Many factors affect how you supplement each diet including:

- Storage and handling conditions.

- Health status of the herd.

- Genetic potential of pigs.

- Voluntary feed intake factors.

Our recommendations should meet the vitamin and trace mineral needs of most pigs under commercial conditions.

Vitamin and mineral premixes

Premixes differ in addition rates and nutrient content. There’s no one correct addition rate or nutrient content. Evaluate premixes based on the total amount and form of each nutrient provided to one ton of feed. Vitamin and trace mineral allowances in table 10 show the amount of nutrient provided per ton of final diet.

Table 10. Suggested vitamin and trace mineral allowances

| Stage of Production | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactation, Gestation/boars, Replacement stock | Starter | Grower/ Finisher | ||

| Vitamin Premixes: | Amount/ton of diet | Suggested Sources | ||

| Vitamin A, IU | 6,000,000 | 6,000,000 | 4,000,000 | Vitamin A palmitate-gelatin coated |

| Vitamin D3, IU | 1,500,000 | 1,500,000 | 672,000 | Vitamin D3-stabilized |

| Vitamin E, IU | 30,000a | 30,000a | 21,000 | dl-tocopheryl acetate |

| Vitamin K, mg | 4,000 | 4,000 | 2,600 | Menadione sodium bisulfite |

| Riboflavin, mg | 6,000 | 6,000 | 4,000 | Riboflavin |

| Niacin, mg | 36,000 | 36,000 | 24,000 | Nicotinamide |

| Pantothenic acid, mg | 24,000 | 24,000 | 16,000 | Calcium pantothenate |

| Vitamin B12, mg | 30 | 30 | 18 | Vitamin B12 in mannitol (0.1%) |

| Pyridoxine, mg | 800 | 800 | 0 | Pyridoxine HCl |

| Thiamin, mg | 1,000 | 1,000 | 0 | Thiamine mononitrate |

| Folic acid, mg | 1,000 | 0 | 0 | Folic acid |

| Biotin, mg | 200 | 0 | 0 | D-Biotin |

| Choline, mg | 530,000 | 0 | 0 | Choline chloride (60%) |

| Trace Mineral Premixes: | ||||

| Copper, g | 8 | 8 | 3.6 | CuSO4•5H2O |

| Iodine, g | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | KlO4 |

| Iron, g | 90 | 90 | 54 | FeSO4•2H2O |

| Manganese, g | 27 | 27 | 1.8 | MnSO4•H2O |

| Selenium, mg | 90 | 272b | 90 | NaSeO3 or NaSeO4 |

| Zinc, g | 90 | 90 | 54 | ZnO (80% Zn) |

aIf fat is added to diet, increase to 40,000 IU/ton of diet.

bThe final diet concentration of selenium will be 0.3 ppm, which is the legal limit for pigs up to 40 lbs. body weight at this writing.

Non-nutritive feed additives

In addition to antibiotics, there are numerous additives producers use to:

- Increase the pigs’ willingness to eat the diet.

- Keep the quality of the diet.

- Improve digestion and utilization of the diet.

Some of these additives include:

- Probiotics

- Flavors

- Sweeteners

- Pellet binders

- Clays

- Antioxidants

- Mold preventers

- Enzymes

- Organic acids

- Yucca extract

- Electrolytes

Contact us or your nutritionist for more information on the use and effectiveness of feed additives.

|

Conversion factors

1 lb = 454 grams (g)

1 kilogram (kg) = 1000 grams = 2.2 lb

1 gram = 1000 milligrams (mg)

1 megacalorie (Mcal) = 1000 kilocalories (kcal)

1 milligram = 1000 micrograms (mcg)

1 mg/kg = 1 part per million (ppm)

1 inch = 2.54 centimeters

1 IU = 1 USP

To convert from % to ppm, move four decimal places to the right.

(.05% = 500 ppm)

To convert from ppm to %, move four decimal places to the left.

(40 ppm = .004%)

Determining lean gain for pigs

You need:

- Pig identity (ear notch or tag)

- Initial weight and date weighed (obtained at 40 to 70 pounds)

- Carcass data

- When optical probe (e.g., Fat-O-Meater) information is available:

- Hot carcass weight (HCW), lb

- Backfat depth (BF), in.

- Loin eye depth (LED), in.

- When optical probe (e.g., Fat-O-Meater) information is available:

-or-

-

- When carcasses are ribbed:

- Adjusted hot carcass weight, lb

- Loin muscle area, sq. in.

- 10th rib backfat depth, in.

- When carcasses are ribbed:

-or-

-

- When carcasses are not ribbed:

- Adjusted hot carcass weight, lb

- Carcass muscling score (1 = thin, 2 = medium, 3 = thick)

- Last rib backfat depth, in.

- Sex code (barrow = 0, gilt = 1)

- When carcasses are not ribbed:

- Days on test from initial weight to market weight

Calculating lean gain per day using equations taken from NPPC, 1991:

Daily lean gain = (Carcass muscle – initial muscle)÷ Days on test

Initial muscle (lb) = [0.418× initial live weight (lb)] – 3.65

For Fat-O-Meater information:

Carcass muscle (lb) = 2.87 + [0.469× adj. hot carcass weight (lb)] + [9.824× loin muscle depth (in)] – [18.47× fat depth (in)]

If the packer provides backfat and loin muscle depth in centimeters, convert them to inches (1 centimeter = 0.394 in.).

For ribbed carcasses:

Carcass muscle (lb) = 7.231 + [0.437×adj. hot carcass weight (lb)] + [3.877× 10th rib loin muscle area (sq. in.)] – [18.746× 10th rib fat depth (in)]

For unribbed carcasses:

Carcass muscle (lb) = 8.179 + [0.427× adj. hot carcass weight (lb)] + (6.290× carcass muscle score*) + (3.858× sex code**) – [15.596× last rib fat depth (in)]

*Carcass muscle scores: 1 = thin, 2 = intermediate, 3 = thick

**Barrow = 0, Gilt = 1

Example calculation

Pig information:

- Initial weight = 50 lb

- Days on test = 109

- Hot carcass weight = 180 lb

- Fat-O-Meater measurements: LED = 3.15 in BF = 0.8 in

Initial muscle = (0.418× 50 lb) – 3.65 = 17.25 lb

Carcass muscle = 2.827 + (0.469× 180 lb) + (9.824× 3.15 in) – (18.470× 0.8 in) = 103.4 lb

Daily lean gain = (103.4 lb – 17.25 lb)÷ 109 days = 0.79 lb

Bergsrud, F. and J. Linn. 1989. Water quality for livestock and poultry. Minnesota Extension Publication FO-1864. Minnesota Extension Service, St. Paul, MN.

Johnston, L.J. and J.D. Hawton. 1991. Quality control of on-farm swine feed manufacture. Minnesota Extension Publication FO-5639. Minnesota Extension Service, St. Paul, MN.

Kerber, J.A., J. Shurson, and J. Pettigrew. 1993. On-farm procedures for monitoring pig growth. Univ. of MN Swine Day Proceedings. pg. 58.

Midwest Plan Service. 1983. Swine Housing and Equipment Handbook. Fourth edition, MPWS-8.

Miller, E.R., D.E. Ullrey and A.J. Lewis (Eds.). 1991. Swine Nutrition. Butterworth-Heinemann, Boston.

National Pork Producers Council. 1991. “Procedures to evaluate market hogs.” National Pork Producers Council, Des Moines, Iowa.

Pettigrew, J.E. 1993. Amino acid nutrition of gestating and lactating sows. Biokyowa Technical Review – 5. Nutri-Quest, Inc., Chesterfield, Missouri.

Pork Industry Handbook. Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service. West Lafayette, IN (Contact your local County Extension Office for order blanks and information).

Stahly, T.S. 1991. Amino acids in growing, finishing and breeding swine. Proceedings of the Animal Nutrition Institute of the National Feed Ingredients Association.

Williams, W.D., G.L. Cromwell, T.S. Stahly and J.R. Overfield. 1984. The lysine requirement of the growing boar versus barrow. J. Anim. Sci. 58:657.

Zimmerman, D.R. 1986. Role of subtherapeutic levels of antimicrobials in pig production. J. Anim. Sci. 62 (Suppl. 3):6.