Performance gap between market gilts and barrows costs integrated operations $5.12 per gilt

About 50% of pig production is made up of market gilts, and gilts do not perform as consistently as barrows. Two university researchers recently completed a review of available literature and identified clearly defined performance gaps between barrows and gilts in growth performance, carcass composition and meat quality and quantified the economic value of those differences.

Dr. Jason Woodworth, a nutritionist at Kansas State University (KSU) and Dr. Ben Bohrer, a meat scientist at The Ohio State University, conducted a statistical analysis of the combined results of 34 peer-reviewed scientific studies1 representing almost 16,000 pigs.

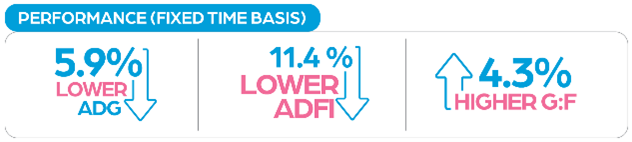

From a live performance standpoint, the study showed gilts were associated with 5.9% lower average daily gain, 11.4% lower average daily feed intake and 4.3% better feed efficiency rate compared with barrows.1

Loss to estrus development – the cause of the performance gap between gilts and barrows

Comparison illustrating female reproductive tract of market weight gilts; pre-pubertal (left) and cycling (right). Final report: TI-06444 (project 20PRGIMV-01-04)

Genetic selection for earlier maturing gilts in the breeding herd creates the possibility for development of estrus in market gilts. Rodrigues et al. (2018) showed that gilts showing estrus had 5.5 times heavier ovaries and 13.9 times heavier uteri compared to non-cycling gilts.

The weight of the female reproductive tract for market gilts slaughtered at 285 lbs live weight was reported by Boler et al. (2014) to weigh 1.39 lbs. Other research shows that either performed oophorectomies, the surgical removal of the ovaries, or immunological suppression of ovarian activity can reduce the weight of the female reproductive tract of market gilts by up to 75%.2

Dr. Woodworth believes if the nutrients can be used toward lean growth rather than development of the female reproductive tract, it will be a more efficient process that is likely connected to the 5% advantage in average daily gain seen in barrows compared to gilts.

“Anytime you’re diverting energy, the animal is going to lose performance,” Dr. Woodworth said. “While the industry seems to just accept the lost performance associated with gilts, there may be opportunities through technology to improve that deficit. The goal is to narrow the gap from a performance standpoint, as well as from a financial standpoint between gilts and barrows as it could make a big difference in profit potential for producers.”

Carcass composition and quality1

Gilts are typically trimmer than barrows. The review indicates gilts typically have 11.7% less back fat, 15.2% less marbling, 2–3 points higher iodine value and 4.5% higher lean percentage. Considering carcass weight, gilt carcasses are approximately 4.8 pounds lighter when compared with barrows.

“It’s important that we fully describe the improved leanness observed in gilts compared to barrows because leaner carcasses have historically been thought of as a good thing. Oftentimes, there is a lean index system that will pay producers more for leaner carcasses,” Dr. Bohrer explained. “However, extremely low levels of back fat, for example carcasses with less than a half-inch of back fat, creates challenges with fabricating several merchandised cuts such as loins and bellies which can result in lost value for meat processors.”

In terms of marbling, gilts have less marbling compared with barrows – in the range of 0.5% intramuscular fat (IMF) or half of a marbling score unit. A 2- to 3-point higher iodine value has also been reported in gilts compared with barrows which is indicative of softer fat.

The Gilt Gap in dollars and cents1

Assuming a fixed time scenario and the slower growth rate, lighter carcass weight and poorer meat quality of gilts when compared with barrows, a $5.12 loss in value is estimated for integrated operations. Looking specifically at the production side – not including carcass and meat quality characteristics – there is a $3.66 loss in value for gilts compared with physically castrated barrows.

“Overall, gilt carcasses are less valuable to the processor than barrow carcasses, and the $5.12 estimated loss doesn’t account for profitability associated with fabrication beyond primal pieces,” explained Dr. Bohrer. “These losses would add up very quickly for a swine operator of any size or scale. Ideally, it would make sense for the swine industry to begin managing gilts differently than barrows to close the gap in economic value.”

“At Zoetis pork, we’re excited about this research review and its implication to producers and integrators in terms of capturing the lost value in gilts,” adds Dr. Brian Payne, Zoetis regional business director. “We’re looking forward to partnering with our customers as we bring new solutions to help close the gilt gap. In fact, our plans are to share new innovation in this area during the World Pork Expo this year.”

Learn more about The Gilt Gap at www.builtforthegilt.com

References

1Woodworth, J., et al. (2021). Characterizing the differences between barrow and gilt growth performance, carcass composition, and meat quality. KSU Applied Swine Nutrition Department.

2Poulsen Nautrup, B, et al., Res Vet Sci, 2020

Rodrigues, LA, et al., Animal, 2019

Boler, D, et al., J Anim Sci, 2014

*Assuming market price = $75/cwt, gilts HCW = -2.2%, premium price = +15% over base price