By Cait Brown

When Ed and Elizabeth Stevermer began construction on their southern Minnesota farmstead in the summer of 1916, they may have dreamed of little else aside from completing the project and getting settled. As it turns out, they were also building a legacy that would carry on through multiple generations.

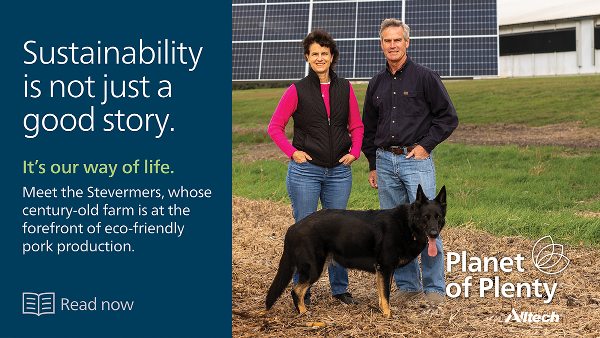

The aptly named Trails End Farm, located near the small town of Easton, has remained family-owned and operated — with a particular emphasis on pig production — for over 100 years. Today, it is run by Ed and Elizabeth’s grandson, Dale, and his wife, Lori, who took over from Dale’s parents roughly 30 years ago.

A match made in hog heaven

Lori was raised some 35 miles away from her future abode, on a farm where her family maintained dairy cows and pigs. At 18, Lori set off for the University of Minnesota with ambitions of becoming a veterinary technician. Later, after changing her mind, she went on to graduate with an animal science degree.

With her brother taking over their family farm, Lori went into feed sales, initially working for a company called Wayne Feeds — a decision that would ultimately change the trajectory of her life.

When asked how she and Dale met, Lori said, “I was out, like every good salesperson, developing my territory and making cold calls, and I happened to stop at a farm near Easton, where I was visiting with a nice farmer about buying feed. I was interested in getting him to do a starter trial with his pigs, and he said, ‘Well, I’m going on vacation. Would you be willing to talk to my son about this instead?’

“I said, ‘Sure, why not?’” Lori continued. “As it turns out, I was visiting with Bernie Stevermer — Dale’s dad — and you can probably guess who the son was that he wanted me to speak with in his place.

“We’ve been married for 32 years this November, and virtually every day, we can wake up, look out the window and see the very spot where we first met,” she said.

Careful resource management creates opportunities for growth

After attending Iowa State University and working in the finance industry for a few years, Dale returned to Trails End in the late 1980s. The farm was primarily a farrow-to-finish operation, home to around 130 sows. In 2016, Dale and Lori decided to sell the sows and convert their farrowing buildings to finishing barns, where they now grow pigs for Compart Family Farms one of the largest family-owned swine genetics businesses in the midwestern United States.

Giving up ownership of the sows — and adding a dependable income stream — allowed the Stevermers to focus less on the farm’s capital needs, which gave them time to concentrate on higher-level management of the farm. It also expanded their operation: At any given time, they now have around 2,000 pigs on-site, which will be raised from 40 pounds to a market weight of 290 pounds.

“I think one of the things that we always wanted to do is to have the ability to adapt our business — and that’s part of sustainability, right? Sustainability isn’t just about resource management; it’s about business longevity, too,” Lori said.

“As single-family operators, there was a great deal of work involved and some disease challenges that were consistently affecting productivity, so making this switch has been significantly impactful for us,” Dale added.

Embracing technology to improve pig production

When it comes to farming, the Stevermers have long considered themselves open-minded and willing to try new things, particularly if an opportunity to improve their production procedures presents itself.

They have adopted various science-based production practices to help manage the pigs, including bringing them indoors to protect them from fluctuating temperatures and disease, as well as utilizing technology in their barns to provide a more consistent climate and improved air quality.

“Today, we use sensors and can remotely monitor temperature and water consumption so that we can intervene sooner if there’s been a change,” Dale said.

Over the past several years, Dale and Lori have implemented several regenerative agriculture practices that improve soil health, such as utilizing cover crops and conducting no-till practices on their 450 acres, in addition to taking steps aimed at improving air quality. To date, they have dedicated nearly 30 acres to this last endeavor, setting aside 18 of those acres for growing trees, 8 acres for buffer grasses and waterways, and 1 acre to become a pollinator habitat.

The Stevermers are also Pork Quality Assurance Plus (PQA Plus)-certified through the National Pork Board. This education and certification program is designed to help producers continually improve their pig production practices. Additionally, the Stevermers believe strongly in the We Care Responsible Pork Initiative, which similarly focuses on food and worker safety, animal well-being, environmental stewardship, public health and contributions to the local community.

“As pig farmers, we have one of the most honorable professions in the world: We produce food for others,” Lori said. “Dale and I take that very seriously, and we want to make sure the food we produce is safe and made with respect for both the animal and the environment.”

Analyzing on-farm data leads to precise, more sustainable farm management

The utilization of precision ag software has enabled the Stevermers to take advantage of yield monitoring, a technique that uses GPS data to analyze variables such as crop yield and moisture content in a particular field. Yield monitoring allows farmers to gain valuable information about their crops and the soil health of their fields while simultaneously developing site-specific crop management.

“The crop and animal cycle continues to become more refined,” Dale explained. “Today, we’re able to test the manure and quantify its nutrient profile. We also test our soils, and — using GPS production data — we apply varying amounts of manure to the ground depending on what is needed for nutrients. We balance our nutrient inputs with anticipated production levels.

“Manure has always been a valuable nutrient source, but the ability to refine the application based on soil health and crop needs has become more sophisticated due to the technology we now have at our fingertips,” he continued.

Dale works with a third-party verifier called Sustainable Environmental Consultants (SEC), which helps collect and analyze data to assess and track Trails End’s progress toward achieving its sustainability goals. He was introduced to SEC through a National Pork Board sustainability pilot project aimed at aggregating farm data on manure handling and usage.

SEC’s verified results have provided several valuable insights.

“Results from the 151 operations that have participated show an average of a $138 per-acre-reduction in fertilizer costs due to using swine manure and an average of 0.3 tons of carbon per acre sequestered, plus an 80% reduction in soil erosion,” Dale said.

The Stevermers have used their farm’s SEC reports to examine overall trends and identify areas of potential improvement. This has led to the installation of solar panels, as well as a flow meter and control system on the farm’s manure tank.

“These efforts are really delivering quantifiable information in terms of how our practices are positively affecting things like decreased soil loss and lower greenhouse gas emissions,” Dale said. “It’s something that helps not just tell a story about agriculture — I think it also lets people know that we hold commonly shared values when it comes to caring about the environment. We truly want to conserve natural resources and use them more wisely, and we hope it will encourage other farms to adopt similar practices.”

True pork industry advocates

When Dale and Lori aren’t on the farm, and when Lori — who serves as the marketing manager for Hubbard Feeds — isn’t at work, they can often be found advocating for agriculture on state and national pork industry boards.

Dale spent seven years as part of the Minnesota Pork Board and is a past president of the organization. He currently serves on a research and educational advisory board for the Minnesota Department of Agriculture. A member of the National Pork Board, Dale has also served on the board’s Soil Health and Water Quality Task Force and budget committee.

Lori currently serves as vice president of the National Pork Producers Council’s board of directors. Her previous experience includes nine years on the executive board of the Minnesota Pork Producers Association — including a stint as board president — along with various state and national committees.

“These advocacy organizations, and others like them, help generate ideas and actions on behalf of agriculture by people who care about the industry,” Lori said.

“There’s a famous quote that states, ‘The world is run by those who show up,’” she continued. “Animal agriculture is produced by less than 1% of the population. If those of us who know farming don’t show up, we risk agriculture being run by people who don’t know it or — worse yet — want to get rid of it.”

The pork industry is a significant contributor to the overall U.S. economy. In 2021, over 66,000 U.S. pork producers marketed more than 140 million hogs valued at over $28 billion in gross cash receipts, according to the National Pork Producers Council. The combined economic contribution from U.S. pig production and pork processing supports more than $178 billion of direct, indirect and induced sales – and over 613,000 jobs.

Family farms like Trails End comprise 96% of all U.S. farms with hogs and account for 81% of the country’s pig inventory, according to the 2017 Census of Agriculture Farm Typology report. That’s one of the reasons the Stevermers are passionate about advocating for agriculture, improving pig production practices through education, and showing consumers and public officials the value of farming.

“Another issue we like to focus on is reminding consumers that pork is healthy, safe and nutritious,” Lori said.

Placing an emphasis on both business and environmental sustainability helps ensure the future of the industry for the next generation, who will work to meet the nutritional demands of the world’s growing population.

“We need the next generation of farmers and advocates to show up for agriculture,” Lori said. “Without them, much would be lost. If producers like us don’t help to set them up for success, who will?”