Source: Bloomberg

China has been long obsessed with finding ways to ensure there is enough food for its population, and with good reason.

With almost a fifth of the world’s people, limited farmland and the increasing challenge of climate change, President Xi Jinping’s government has exhorted farmers to maximize harvests and consumers to minimize waste. It’s built up huge stockpiles to cope with shortages and created new seeds to boost output.

Even so, the country still buys about 60% of all the soybeans that are traded internationally, and ranks as the biggest corn and barley importer. It has also recently emerged as one of the world’s largest wheat buyers. That makes soaring global crop costs and, potentially, a looming world food crisis very much a matter of concern for the government, especially in terms of how local prices perform. Here are some of the food security challenges China faces:

Soybeans, Edible Oils

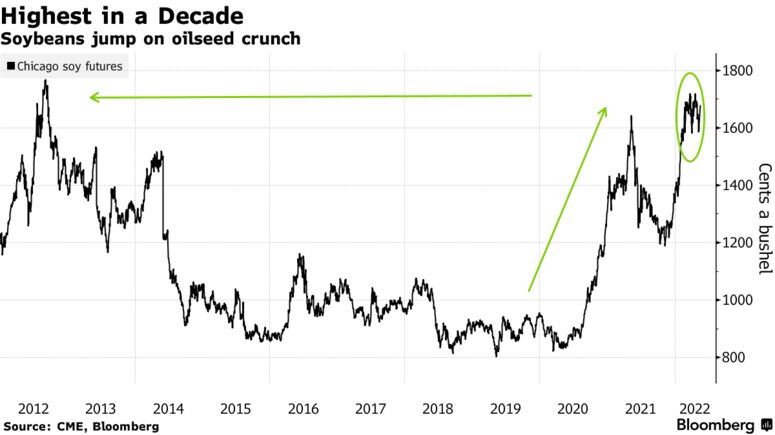

China’s local consumption of soybeans is almost as large as the entire US harvest, and the country has to import about 85% of its needs. The beans are crushed into edible oil for cooking and other food uses, and into feed for its hog population, the world’s largest. Global soybean prices have doubled in the past two years on dry weather in South America and a shortage of oil-bearing seeds. Unless the US has a bumper crop this year, they could go even higher.

“Soybeans carry the biggest inflationary risk,” said Jim Huang, head of China-America Commodity Data Analytics. Rising prices of crude oil and freight, as well as the weakening yuan, are worsening the situation, he said by email.

China is also the biggest importer of palm oil after India and a major buyer of sunflower oil. Global cooking oil prices have soared to records on drought, labor shortages and Russia’s war in Ukraine. The latest leg-up came after top exporter Indonesia banned palm oil shipments.

The government is making a big push to boost soybean production, with the crop poised to jump 19% in 2022-23. But with output so low compared with consumption, that isn’t going to make much of an impression on imports.

Corn

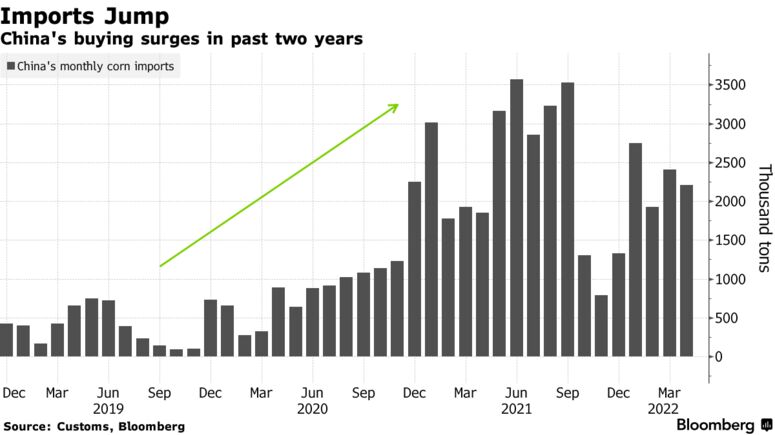

For a long time, China didn’t buy much corn overseas, but in recent years that started to change with the country emerging as the world’s biggest importer, driven by the need to replenish inventories and feed a rapidly expanding hog population. The surge in buying, much of it from the US, its geopolitical rival, spurred China to boost its focus on self-sufficiency as a national security goal.

Unlike soybeans, however, where the country has been highly dependent on foreign supplies, corn imports only accounted for about 10% of domestic consumption in the 2020-21 year, and that percentage is on track to shrink to about 6% by 2022-23, according to data from the US Department of Agriculture.

China buys quite a bit of corn from Ukraine, with the Black Sea nation supplying about 30% of shipments last year, its second-biggest supplier. But that trade has been throttled by the Russian invasion, and is one of the possible reasons behind an expected decline in imports in the coming year.

Wheat

The world’s supply of wheat is under threat as everything from war to drought, floods and heat waves cut production. Global wheat prices soared to a record in March after Russia invaded Ukraine, and they are 80% more expensive than they were a year earlier, helping push global food costs to the highest ever.

Like corn, the country’s dependence on imports is low at about 7% of consumption in 2021-22. That still makes it one of the world’s top buyers along with Indonesia, Egypt and Turkey. There has been concern over production in China, and at one point a top official said the country could face the worst crop conditions in history after record-breaking floods last year. Authorities are also investigating if there’s any illegal destruction of the crop after videos showing immature wheat being destroyed or cut down went viral on social media.

What’s Next

China has built up huge stockpiles of wheat, rice and corn, and according to USDA estimates, the country holds at least half, if not more, of global inventories for these commodities. The government will release stockpiles if needed to alleviate any food inflation or shortages, said Iris Pang, chief economist for Greater China at ING Bank. Fertilizer costs are a concern and could push up food inflation, but “not to a worrying situation,” she added.

Over the longer term, Beijing has called for stronger measures to stabilize production, with two priorities: new seeds and protection of arable land. It’s seeking to develop genetically modified seeds to boost yields, and wants to stop farmland being used for construction or turned into golf courses.