I’ve always enjoyed taking concepts from other disciplines and applying them to pig production. In this post, I’ll borrow a concept from economics…Goodhart’s law, which is frequently described like this: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” Record keeping and metrics are an important tool in modern swine production. Our ability to keep accurate records and derive insights from those records through analysis has been a driving factor in the remarkable increases in efficiency that we’ve all witnessed in recent decades. I hope this post will convey, however, the importance of ensuring that metrics remain metrics and don’t become goals.

Goodhart’s law is attributed to British Economist Charles Goodhart who used it to critique 1970’s monetary policy in the UK. Originally, it was expressed like this in a 1975 paper by Goodhart… “Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.” It was later modified for more general application and is now usually described as “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

Examples of Goodhart’s law are easy to identify across a wide range of disciplines/applications. For example, in law enforcement, the success of police departments is often based on a low crime rate. A focus on the crime rate, however, could drive police departments to discourage citizens from reporting crimes or to reclassify crimes as less serious offenses. Sticking with the legal theme, prosecutors are often judged on their conviction rates which can encourage them to avoid prosecuting challenging cases, preferring to settle these cases out of court or forgo prosecution altogether. Obviously, neither of these examples are likely to further the ultimate goal of law enforcement and the justice system…to create safer communities and might very well make communities less safe.

There are several general business examples as well. It is common to compensate and reward salespeople based on sales volume. This can encourage salespeople to be overly aggressive on pricing resulting in lower revenue for the business. In some extreme cases, at the end of a time period, salespeople might even be incentivized to sell product at a loss in order to achieve sales volume targets. Obviously, this is counterproductive if we assume that a primary actual goal of the business is to increase profits.

By now, anyone with experience in the swine industry will be thinking of examples. I think Goodhart’s law surfaces in two primary ways in our industry 1) incentive programs and 2) optimizing for common metrics. I think a better understanding of the risks of these tendencies can help the industry continue to develop. I also think it’s important to recognize the role some of these metrics have played in the development of our industry in recent years. We’ve come a long way and these metrics have been an important factor in getting us to this point. It’s important to recognize this context lest my criticisms seem overly harsh.

Incentive Programs:

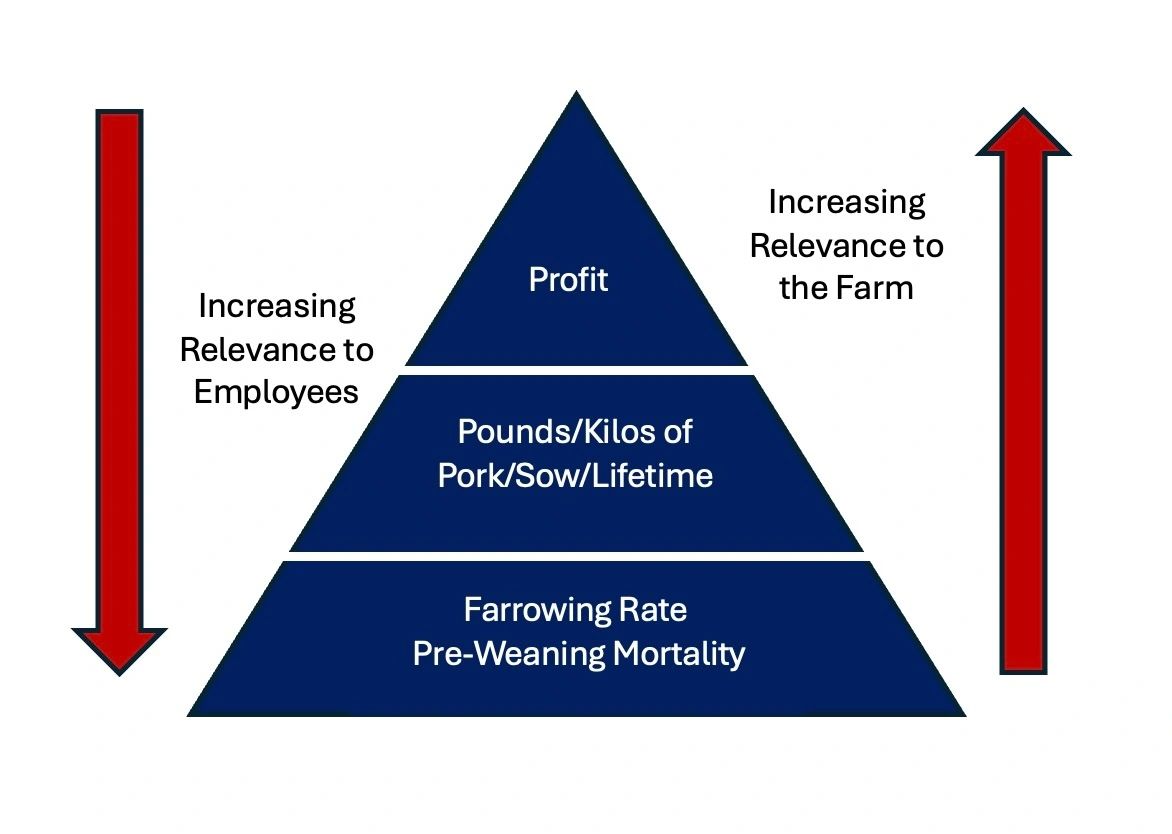

I have written extensively, including here, about my frustrations with incentive programs. Most of this frustration is due to the difficulty of establishing programs that send consistently good signals without also incentivizing behavior that is damaging or counterproductive. Much of this problem is a result of the tension between metrics that are most meaningful to the business and those that are most meaningful to individual employees and teams on farm. To illustrate this issue, I use the metric pyramid. As we go up the pyramid, metrics become more relevant to the business itself. At the top of the pyramid is the ultimate metric, profitability. At the bottom of the pyramid are metrics that are meaningful to frontline employees, things they can directly impact like farrowing rate and pre-weaning mortality.

The problem with metrics at the top of the pyramid is that it is difficult for frontline employees to directly connect their day-to-day activities with these outcomes. There are many factors that determine profitability and some of them are completely outside of the control of employees. Even for those that are influenced by front line employees’ actions, it is sometimes difficult for employees to make those connections. These metrics are extraordinarily important, however, for farm owners and executives who are focused on farm/system profitability.

Metrics at the bottom of the pyramid have the advantage of being easily influenced by individual employees and teams. It’s easy for employees to understand how they can impact farrowing rate and pre-weaning mortality. While not entirely within their control, by effectively implementing sound production practices and closely following procedures, they can have a positive impact on increasing farrowing rate and reducing pre-weaning mortality. Obviously, a higher percentage of sows that farrow and fewer dead pigs is a good thing right? Well, yes, but there’s a big but.

Intense focus on these metrics, without proper context, can encourage practices and behaviors that are detrimental to overall farm success. For example, if an employee is paid a bonus on farrowing rate, they might choose to only breed sows and gilts that they are 100% confident are in heat and have a good history of being successfully bred. This could lead them to ignore, and ultimately perhaps cull, sows and gilts that still had a more than acceptable chance of becoming pregnant.

Another very common example is when employees get a bonus for pre-weaning mortality. Employees very quickly realize that if a pig is born weak, they can write it up as born dead. Then it goes down as a stillborn which doesn’t impact their preweaning mortality. If the pig dies, it doesn’t count and if it survives, it cancels out another pig that died unexpectedly. This is obviously problematic when it comes to diagnosing problems because there is a big difference between a pig that was born weak and later died and a pig that was born dead. The diagnosis and potential interventions are completely different. It has gotten to the point that I always ask clients/prospects if they have a pre-weaning mortality incentive before I even look at their records.

Optimizing for Common Metrics:

If someone asks you about how good a sow farm is performing, your answer will probably be to respond, at least in part, with the farm’s Pigs/Sow/Year or PSY. Actually, it’s most likely Pigs/Mated Female/Year, but we don’t like change so we still commonly refer to it as PSY as I will here. This is not at all surprising. PSY is a pretty good metric for evaluating the overall efficiency of a sow farm and since it is such a useful metric, it has become the industry standard way to evaluate sow farm performance.

PSY has become so ingrained in industry culture, it has become not just A way to measure sow farm performance, but, for a lot of people, THE way to measure it. This is where Goodhart’s law comes in and the previously useful metric becomes less useful because it has become the target. Farms and even entire systems have been designed, whether consciously or subconsciously, around optimizing for a single metric. One might argue that entire national programs have been built around PSY optimization. So, if PSY is a good metric for sow farm efficiency, why is this a problem?

While a good metric, PSY has some significant weaknesses. For example, it is concerned only with quantity, not quality. This can encourage employees to send pigs to the nursery or wean to finish farm that don’t meet basic standards. As any nursery/W-F manager will tell you, garbage in/garbage out and some of those pigs will likely get through even a thorough evaluation at the nursery and negatively impact overall production. Most systems don’t get paid for weaned pigs and even those that do will, in most cases, have an incentive for their pigs to perform well in the next phases to keep customers happy.

Another problem with PSY is that it focuses only on the short term. Implicit in this metric is the idea that sow longevity doesn’t matter. We know, however, that sow longevity and maintaining an appropriate parity structure are critical to the long-term viability of the farm. So, optimizing for PSY can sacrifice long term performance for short term gain. This can even influence higher levels of the industry where over focus on PSY can encourage genetic programs and other functions to place undue emphasis on litter size potentially at the expense of other important metrics like pig quality and sow longevity.

I would argue that this can extend even beyond national boundaries. For example, it is my opinion that over focus on PSY has led producers in many European countries to increase litter size beyond the sow’s capability to handle contributing to high labor costs, poor sow longevity and poorer results during the wean to finish period. PSY encourages us to assume that the 16th pig born in the litter is equally as valuable as the 10thor that each pig is as valuable as the average pig. We know, however, that’s not the case. We know that average birth weight goes down as litters get bigger and we know that low birth weight is a contributing factor to mortality and poor performance in the farrowing house and beyond. So, those extra pigs may be less valuable than average and perhaps even not profitable.

On the growing pig side, we see a similar issue with another important metric, Feed:Gain or Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR). FCR is a critical metric in growing pig performance. It gives us an idea of how efficiently feed is being converted into pork. Since feed is by far the biggest cost in pork production, FCR has an outsized impact on profitability. You certainly won’t find me arguing that FCR is not important. Because of its importance and relative ease of measurement/value contribution, FCR ends up driving a large percentage of the focus for wean to finish managers.

The reality, however, is that while important, FCR needs to be balanced against other important metrics like growth rate or average daily gain (ADG). Any nutritionist will tell you the best way to improve FCR is to reduce feed intake. So, nutritional strategies, genetic selection programs and management practices that optimize for FCR ultimately run the risk of reducing feed intake even if it’s not intentional. At some point, the advantage of feed efficiency is offset by reductions in growth rate…hence the need to find an appropriate balance.

While FCR and ADG are about equally easy to measure, evaluating the economic value is much easier for FCR. Most everyone knows how much their feed costs so estimating the value of 1/10th of FCR is pretty straightforward: lbs or kg of feed saved * cost per lb or kg of feed. ADG is a lot different. The value of ADG is derived from either gaining more weight in the same or shorter time period or reaching a target market weight in less time. The relative value of ADG varies depending on space availability and constraints on market weight established by consumers or packers. The reality is that the value of ADG varies from farm to farm within systems and even for the same farms/systems over time as conditions change.

The result is that many farms/systems overemphasize FCR at the expense of ADG and over time, pigs will struggle with the natural ability to eat enough to grow at a sufficient rate. As a result of this diminished appetite, pigs also become less robust and more difficult to manage when faced with stress be it from health challenges, heat or some other source.

Goodhart’s law tell us that when metrics become the goal instead of just a metric, they cease to become a valuable metric. Since PSY and FCR have become goals in and of themselves on many farms and in many systems, we’ve seen challenges emerge. We now have litters that are too big for sows to adequately care for without expensive and labor-intensive supplemental milk and we have growing pigs that have excellent feed efficiency, but slow growth rates. These trends are due in part to the fact that we elevated PSY and FCR to ends themselves instead of metrics to indicate progress towards the ends.

So, what can we do to avoid the negative effects of Goodhart’s law? We need to make sure that we adopt a holistic view of pork production and avoid elevating individual metrics, no matter how good they are, to such a lofty status that producers begin optimizing for the metric instead of the true desired result. This requires the usage of multiple metrics and the use of composite metrics that capture a more holistic view of our progress towards our ultimate goals.

It’s also incredibly important for everyone in the business to have a clear understanding of what exactly those ultimate goals are. One might argue that profit is the ultimate goal, but even profit, if used as the sole metric, can lead a business astray. Focusing exclusively on profit can cause the farm to ignore fundamental responsibilities such as animal welfare, environmental stewardship, compliance with laws and customs and contribution to local communities. No single metric is likely to capture the complexity of an entire business. Instead of searching for one metric, the most successful farms establish a collection of high value metrics that, when considered as a whole, serve as valuable guideposts to overall success.

This content is entirely human generated.

About the Author: Todd Thurman is an International Swine Management Consultant and Founder of Swine Insights International, LLC. Swine Insights is a US-Based provider of consulting and training services to the global pork industry. To learn more about the company, send an email to info@swineinsights.com or visit the website at www.swineinsights.com. To learn more about Mr. Thurman’s speaking and writing, visit www.toddthurman.me